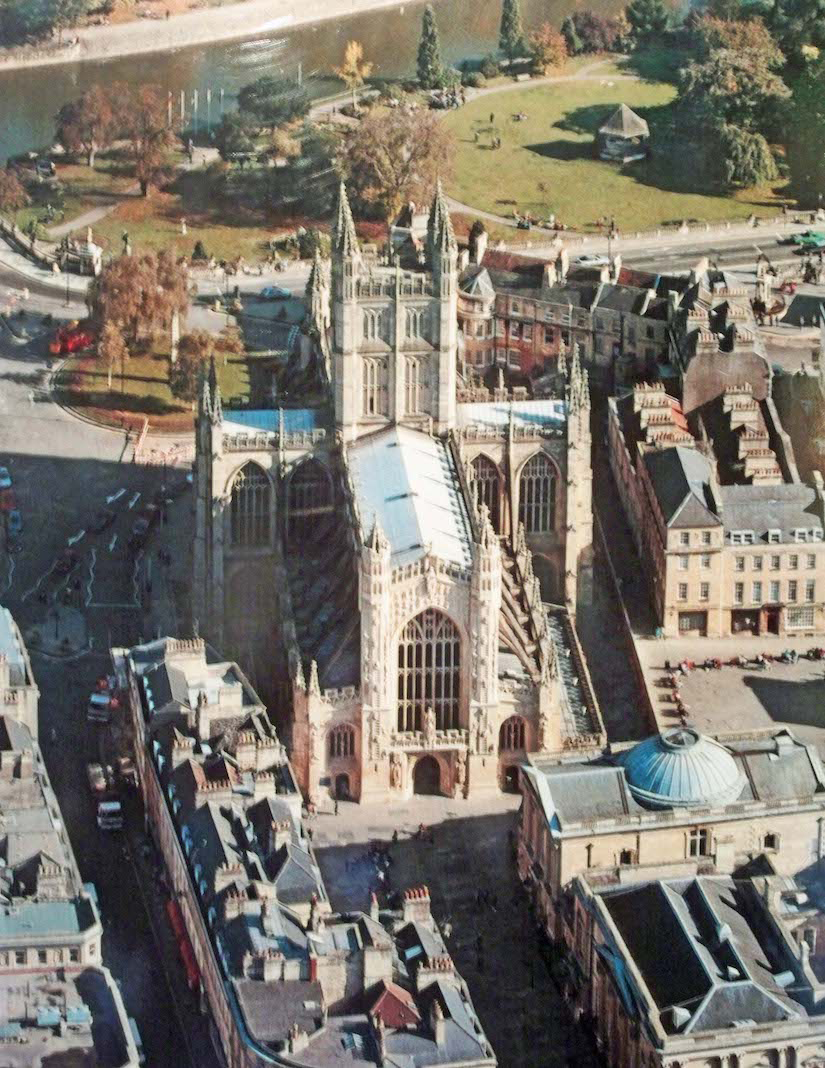

We arrive in Bath from Bristol by train – a journey taking some 40 minutes. We then join the tourist crowd making their way due north along the rather ordinary Manvers Street. With churches in mind, we do notice on our right first the distinguished looking old Baptist Church, and then a little further and more distant, the graceful St John the Evangelist Catholic Church with its tall spire. After a couple of blocks, Manvers Street mysteriously becomes Pierrepont Street , and after a further couple of blocks the street curves around a beautiful park alongside the River Avon. Looking at this aerial view of Bath Abbey, we are entering on the right side. But even now, the Abbey does not look very impressive, being cluttered in on one side by non-de-script buildings. In the view above, we are looking at the Abbey from the West end, and it is from here that we shall start our investigation.

2. WEST WALL RH

This is the West wall – farthest from the River Avon. There is much to notice here, and we shall return, but for now, notice the wonderful West doors with King Henry VII above, sculpted by Sir George Frampton, and flanked by statues of St Peter and St Paul. We shall walk around the Abbey in a clockwise direction, so leading off around to the left.

3. NORTHWEST VIEW RH

The Abbey is built in the perpendicular Gothic style with many tall straight vertical lines. The two layers of windows are large, with clear clerestory windows above, and much stained glass below. We notice the flying buttresses and pinnacles which give stability and decoration to the structure. A tall central bell tower marks the intersection of the main axis of the Abbey with the cross transepts. And here in the midst of a street market, we find a white marble fountain.

4. FOUNTAIN IS

This drinking fountain is called the Rebecca Fountain, or the Temperance Fountain. The fountain depicts a life-size female figure pouring water from an urn into a bowl, with the inscriptions ‘take the water of life freely’, and ‘water is best’. It was erected by the Bath Temperance Association in 1861.

5. CENTRAL TOWER IS WH

Two moods of the central tower, framed by the low parapet wall and pinnacles atop the choir and transept. In 1700 the old ring of six bells was replaced by a new ring of eight. All but the tenor still survive. In 1770 two lighter bells were added to create the first ring of ten bells in the diocese. The tenor was recast in 1870. The abbey’s tower is now home to a ring of ten bells, which are hung unconventionally such that the order of the bells from highest to lowest runs anti-clockwise around the ringing chamber, rather than in the usual clockwise fashion. The tenor weighs 33 cwt (3,721 lb or 1,688 kg). Bath is a noted centre of change ringing in the West Country. How is the tower reached? Each of the corner spiral staircases leads to a door opening to a walkway to the tower along the East to West edges of the gable roof, but the Northeast staircase is the entry which is used. You can join a tour to make the 212 step climb to the tower to view the clock from behind, and the bells.

6. NORTHEAST VIEW W

Continuing our tour, and stepping back, the graceful lines of the Abbey become evident. It is unfortunate that the A3039 Motorway skirts the Abbey so closely at this point. The flying buttresses and pinnacles are characteristics of this Gothic style. The pinnacles are decorative, but also heavily weighted so that the outward thrust on the pillars is directed downwards. [Photo Credit: Wikipedia]

7. EAST WALL PRS

The East view of the Abbey is spoilt by the surrounding encroaching buildings and the traffic. The fickle Bath weather doesn’t help either! The Abbey contains three very large windows. The East window shown here is easily characterised by the two circular features in the top corners.

8. RESURRECTION OF CHRIST WH

There is a walking path right around the Abbey, and we are able to continue our clockwise investigation. We come to the vestry tucked in beside the South transept, and this adjacent statue of the Resurrected Christ. This statue shows Christ at the moment he burst out of his burial wrappings. It was sculpted by local artist Laurence Tyndall, and installed in 2000. The artist says: ‘I made this sculpture of the Resurrected Christ for Bath Abbey in 2000. It was carved on site at the south east corner of Bath Abbey over a nine month period. During these months thousands of spectators had the opportunity to watch me at work. Many also talked to me about life, faith and art. The figure of Jesus breaking the bonds of death is a very potent symbol not only for Christians but for everyone. We would all like to be free of our constraints.’

9. SOUTHWEST VIEW W

At the Southwest corner of the Abbey we find a large ‘parade ground’ space. Revealed here is a large lower storey of the Abbey – the clergy vestry – accessed from the outside by a descending staircase next to the South transept. Later we shall find what appears to be an internal access through to the South transept. At bottom left a skeleton manoeuvres a large tricycle past the Abbey: there is scope for some funny stories here! [Photo Credit: Wikipedia]

10. WEST WALL IS

This brings us back to the ornate West wall: we have completed our circuit of the Abbey, and joined the visiting crowds. Above the West window we see the seated Christ, sculpted by Sir George Frampton. The relief on top of the façade shows the Angelic Choir, in attitudes of adoration, glorifying the Trinity. At the very top of the window, a dove represents the Holy Spirit.

11. WEST WALL AND KING HENRY VII IS W

Why King Henry VII? Sometime around 1499 Oliver King, the powerful Bishop of Bath and Wells, had a dream. King, who also served as Henry VII’s Secretary, saw a vision of angels climbing a ladder to heaven, and heard a voice saying, ‘Let a King restore the church’. The Bishop took this as a heavenly message that he should rebuild the Norman church of Bath Abbey as a great new cathedral. He had the old church destroyed and a grand new edifice begun in Perpendicular style. Rebuilding plans were severely disrupted by Henry VIII, and it was not until 1613 that the building was completed. So in answer to the question, Oliver King was Secretary to King Henry VII who was reigning at the time of the initial rebuilding of the Abbey. Two close-up views of King Henry VII can be seen here. Also, [Right Photo Credit : Wikiwand]

12. WEST DOOR G

During this reconstruction, the solid oak West doors of the Abbey were carved courtesy of, then Bishop of Wells and Bath, Bishop Montagu’s own brother, Lord Chief Justice Sir Henry Montagu. The Montagu coat of arms is prominent on the doors along with the Latin inscription: ‘Ecce quam bonum et quam jucundum est’. (Behold how good and pleasing it is.) To complement the doors, symbols of the Passion are carved in the upper corners above the archway. The doors are functional, but only used for ceremonial purposes. Smaller doors on either side are used for everyday use instead. [Photo Credit: Google]

13. UPPER WEST WALL WH WH

The West window is flanked by two towers. There are twelve standing figures on these towers in vertical groups of three: these are the Twelve Disciples of Jesus.

14. JACOB’S LADDER WH

Also prominently displayed on these two towers are the ladders with angels ascending and descending. These obviously relate to the vision of Bishop Oliver King (#11), as well as the Old Testament story about Jacob’s Ladder in Genesis 28 where Jacob said: ‘Surely the LORD is in this place; and I knew it not.’ And he was afraid, and said: ‘How full of awe is this place! this is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.’ Looking closely, we see that two of the angels are coming down head first! We won’t ask why ... . Some close-ups of the angels can be seen here.

15. NAVE PRS

We enter the Abbey through a Western side door, and gasp in amazement. Such graceful slender vertical construction flowering into an incredible vaulted ceiling. Colourful light fittings, although there is ample natural light streaming through the high nave clerestory windows. And in the distance the colourful East window with its distinctive corner circles.

16. CHANDELIERS PRS WH

The 15 chandeliers, designed by Francis Skidmore in 1870, were adapted to gas in the 1900s and electricity in 1978. However, it was felt that the 1970’s electric fittings detracted from the chandeliers and provided inadequate lighting. In 2013 the chandeliers were fitted with energy-efficient LED lights.

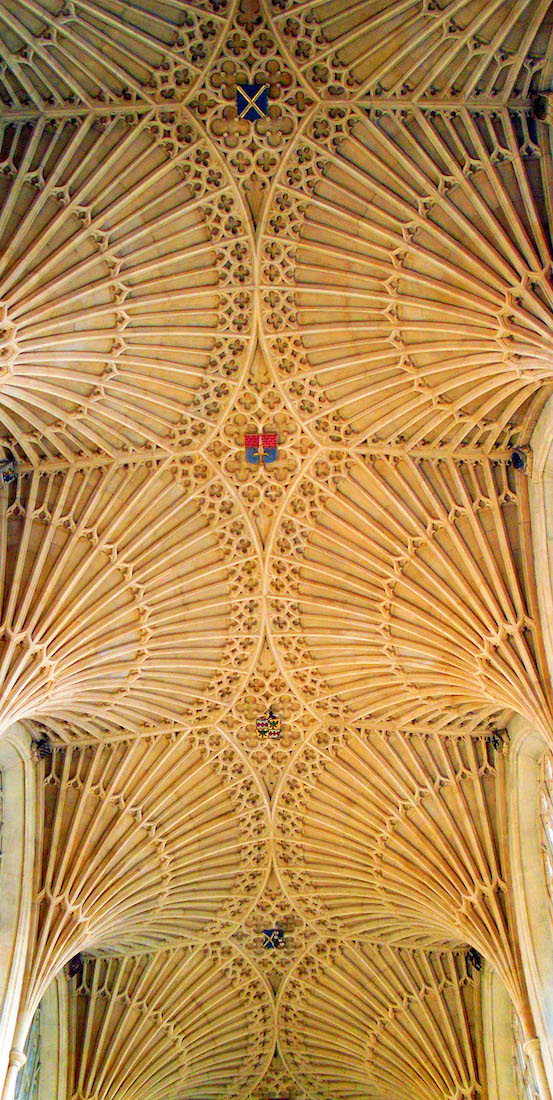

17. NAVE VAULTING WH

The fan vaulting is a feature particularly associated with English Gothic church architecture. As all the ribs in a sequence have the same curvature and rotate around a common vertical axis at equal intervals, they form a perfect conoid resembling a fan. Transferring the weight of the ceiling through numerous narrow ribs rather than fewer and bulkier structures, the fans contribute to a sense of lightness – and simply block less light. They meet at flat (diamond-shaped) spandrels, too, rather than at bulky bosses. Each spandrel has a crest at its centre, including the crests of Bath and the Wells Diocese.

18. AISLE VAULTING RH RH

There is beautiful fan vaulting in the side aisles too, although suitably scaled down in size. A difference here is that at the join of the fans, the spandrels that we saw before are now replaced by pendants: small downward-pointing concave conical features.

19. WEST WALL G

We walk a little way down the nave and turn to face the West wall. There are three stained glass windows before us in this wall. At extreme left we catch sight of the baptismal font; right is a large entry porch, protecting the interior of the Abbey from the Bath weather when this entry door is in use. Various plaques and memorials are arrayed around the West doors, including two large sculptures which we shall examine shortly. The small door on each side leads to a spiral staircase ascending to the roof. [Photo Credit: Google]

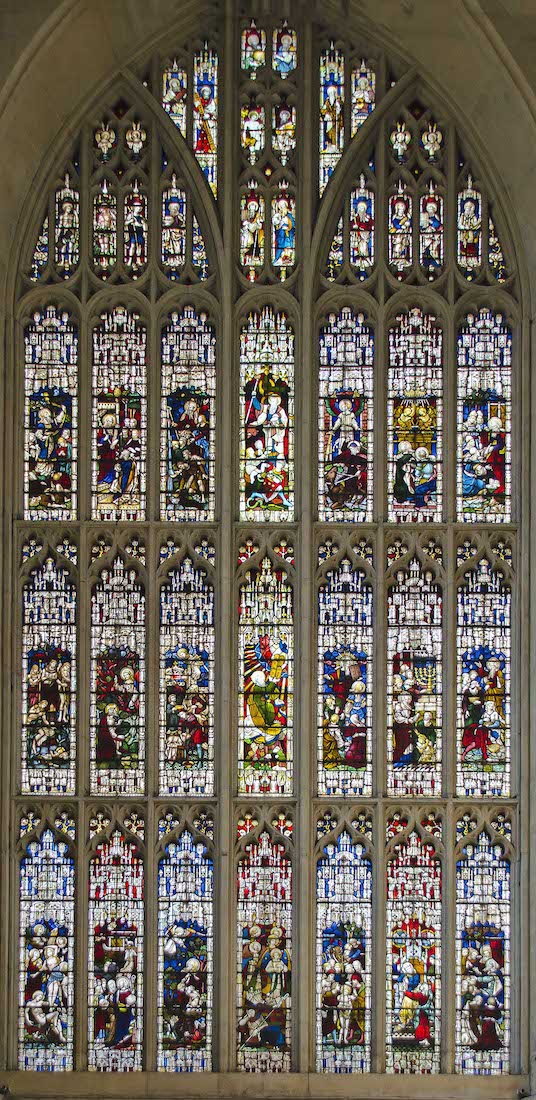

20. WEST WINDOW WH J&J

Here are two views of the Great West Window. The glass is by Clayton and Bell. The window was developed over a number of years from 1872, and not finished until 1894. It depicts scenes from the first five books of the Old Testament.