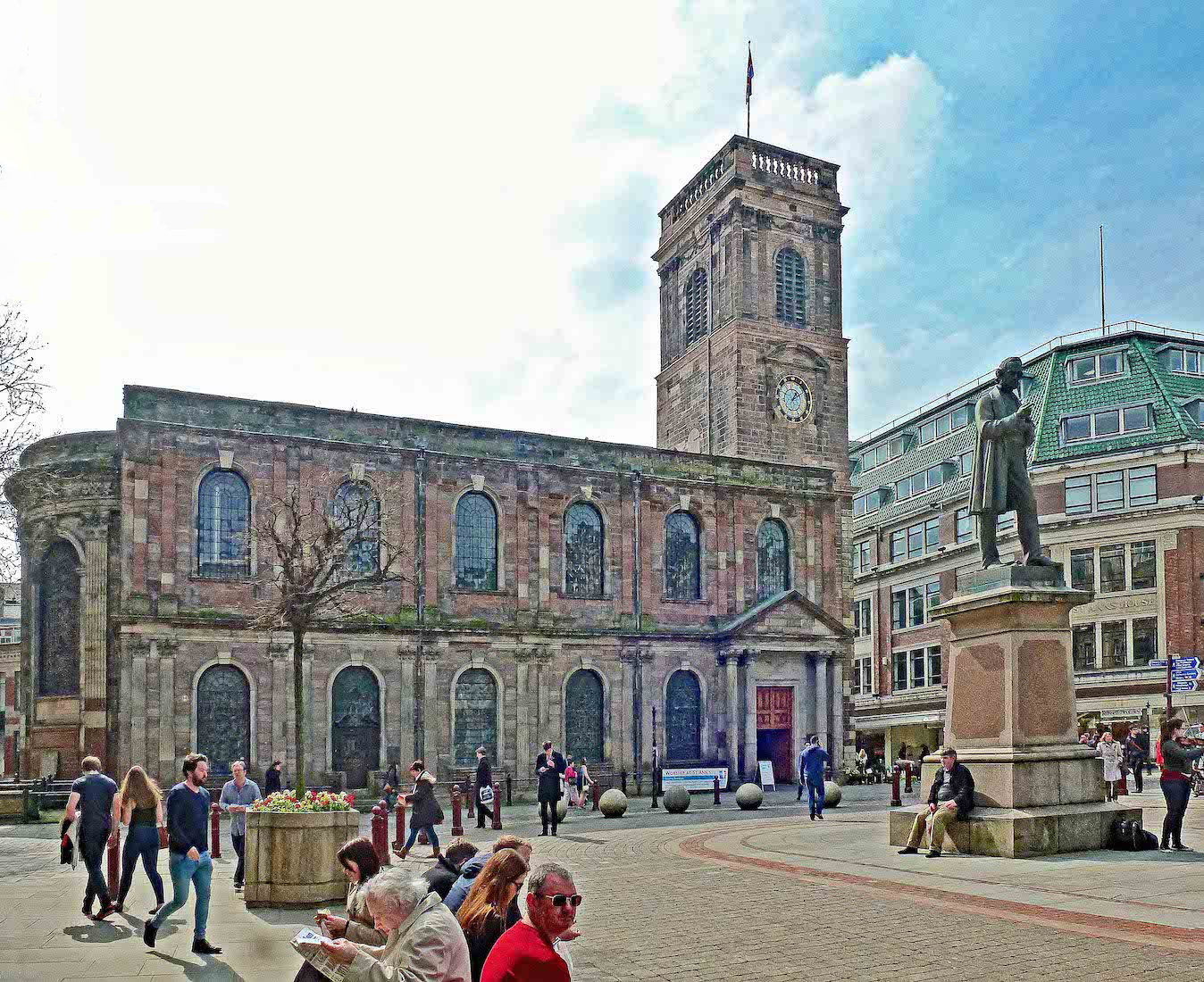

2. APPROACHING THE CHURCH

The Church itself is impressive, built from locally quarried soft red stone, and having had a number of obvious repairs over the years. The large arch windows with their round tops are unusual. The tower at right was once a local landmark, seen from afar, and regarded as the centre of the city. We notice a sleeping figure on a bench behind the concrete balls just to the left of the statue, and there is a small door just to the left of the parked bicycle.

3. HOMELESS CHRIST

The sleeping figure is a bronze sculpture known as ‘Homeless Jesus’, by Canadian sculptor Timothy Schmalz. It depicts Jesus as a homeless person, sleeping on a park bench. The original sculpture was installed at Regis College, University of Toronto, in early 2013, and other casts have since been installed at many places across the world.

4. NORTH DOORWAY

A little further along this wall we come to a small door, well camouflaged in its window surround. There is a metal plaque mounted on the wall to its right. The architectural style of this Church is said to be neoclassical, but the wave like scrolls around this door appear to be something else.

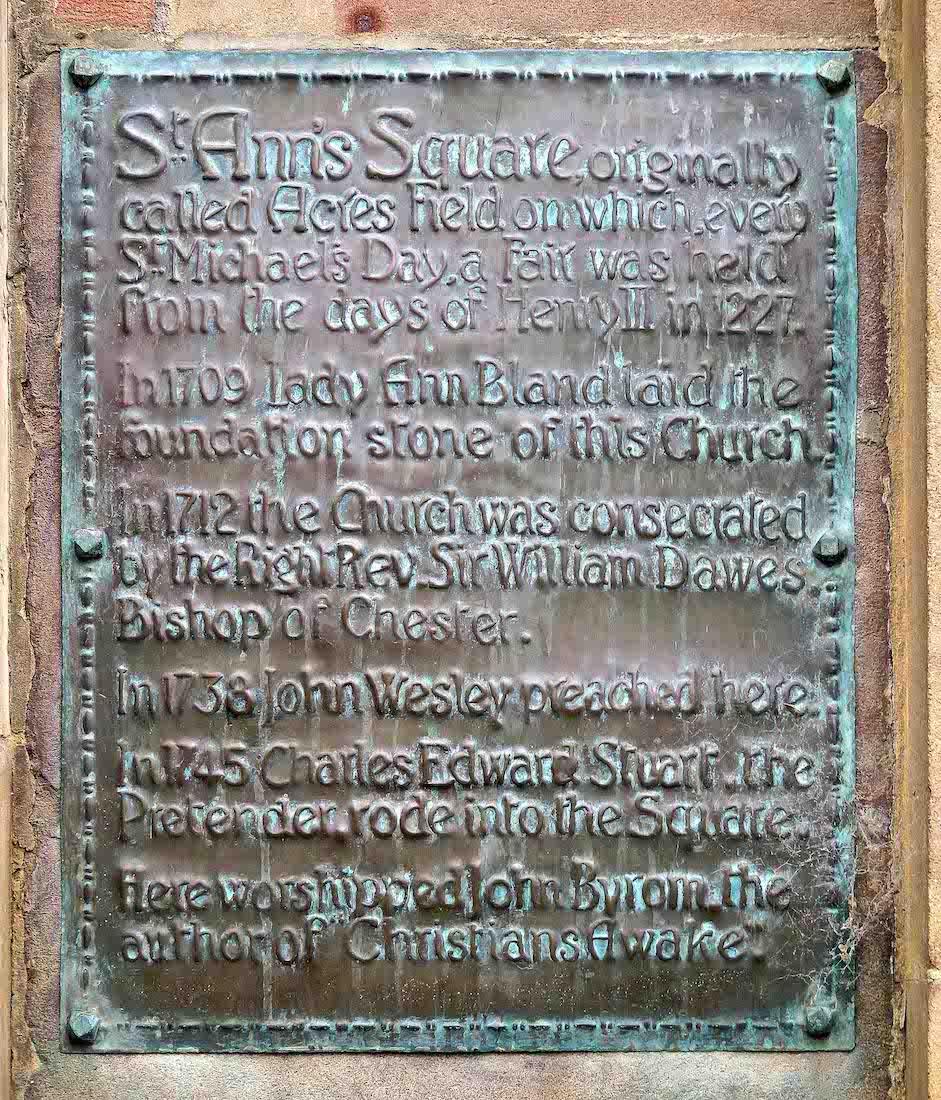

5. DOOR DETAIL AND PLAQUE

The plaque to the right of the door gives some history of the Church and tne Square. Thus in 1709, Lady Ann Bland laid the foundation stone of the Church. In 1712 the Church was consecrated by the Right Revd Sir William Dawes, Bishop of Chester. In 1738, John Wesley preached here. In 1745 Charles Edward Stuart the Pretender rode into the Square. Here worshipped John Byrom, author of ‘Christians Awake’.

6. APSE AND GRAVES

At the East end of the Church there is an apse with stained glass windows. There is also a paved walkway skirting two fenced off areas containing small numbers of graves. The graveyard was partially cleared in 1842 and the majority of the gravestones were removed in 1892, although a few are still visible. The former church yard was paved over and landscaped and is today part of the St Ann’s Square development. These are the last tombs to survive outside city centre places of worship and recall turbulent times and interesting characters.

7. MONUMENTS

Shown here is the Boardman grave, and the grave of Thomas Deacon. Also buried here are some of the family of writer Thomas de Quincey (renowned for his ‘Confessions of an English Opium Eater’ published in 1821). The author isn’t buried here, but his sister Elizabeth is. Elizabeth was his childhood playmate and her death in 1793 etched a permanent tinge of melancholy on her brother’s notoriously delicate character. [CCL Photo Credits: Peter James: Wikimedia; Chinese entry : Wikimedia]

8. APSE

The apse at the East end of the Church contains three attractive stained glass windows which reveal an inner glow as dusk settles. [Photo Credit: Sam Beckwith]

9. SOUTH SIDE

Rounding the apse, we walk back along St Ann’s Lane, viewing the South side of the Church. This is an attractive face with good lighting. It is amazing though how much of the original stonework has been replaced. We shall find the the two nearer bottom windows belong to the Lady Chapel, and are different in character from the rest. [Photo Credit: James Hall]

10. TOWER

So to the West end with the tower and the Southwest entry. After a major refurbishment completed in 2012 , the clock was working, and the Church bell began to ring in the hours – for the first time since 1931. [Photo Credit: Max Hanna]

11. SOUTH ENTRY

The Southwestern entry has a similar design to that on the opposite side, but looks a little less cared for – probably because it is the ‘back’ entrance. [Photo Credit: Mossman19, TripAdvisor] The Church logo, featuring a stylized Cross on a colourful background, appears at several points around the Church.

12. TOWER

Major work was carried out on the tower just shy of the Church’s 100th birthday when an unstable wooden spire was dismantled and replaced with the section of the tower above the clock by an unknown architect – Thomas Harrison perhaps? Much later, the 2011–2012 renovations included the restoration of the North facing clock and renovations inside the tower, which now boasts a new internal roof, new stained glass windows and a new flagpole.

13. NORTH ENTRY

We finally arrive at the Northwestern entry with the detailed foliage decoration at the tops of its Corinthian columns, and make our entry into the Church.

14. NAVE

The entry brings us straight into the back of the spacious nave, which is quite stunning. This is a high space bounded by plain white columns supporting round arches, and with a balcony on three sides. The focus to the front is a raised sanctuary apse with altar, and three large and dramatic stained glass windows. This beautiful and tranquil space in the middle of the bustling city is quite unexpected.

15. NORTH NAVE WALL

We shall begin by exploring the three windows and the various monuments of the North wall. When St Ann’s Church was first constructed, the interior was extremely simple with plain glass windows. However many changes were made during the restoration of the Church by Alfred Waterhouse between 1887 and 1889. These changes included the installation of stained glass windows in the reconstructed chancel and sanctuary.

16. SOLOMON WINDOW

The first window on our left is the Solomon window. This window was fitted in 1937 by the Lancashire District Masonic Guild in memory of Cecil Wilson, Bishop of Middleton. It depicts the Old Testament King holding a model of the temple whilst standing between its pillars. The pediment above the King carries the Masonic coat of arms.

17. JUBILEE WINDOW

The second window is the Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Window by Heaton, Butler & Bayne, dating from 1897. This North aisle window was installed in commemoration of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. After a bomb attack by the IRA on Manchester in 1996 the window was restored in memory of Maria Isabella Blythe Nicholls (1898–1985). The design incorporates the Shepherd slaying a lion between ornate pillars with the Crown and Royal Coat of Arms above. The dates on either side are 1837 (when Victoria came to the throne) and 1897 (the date of the Jubilee).

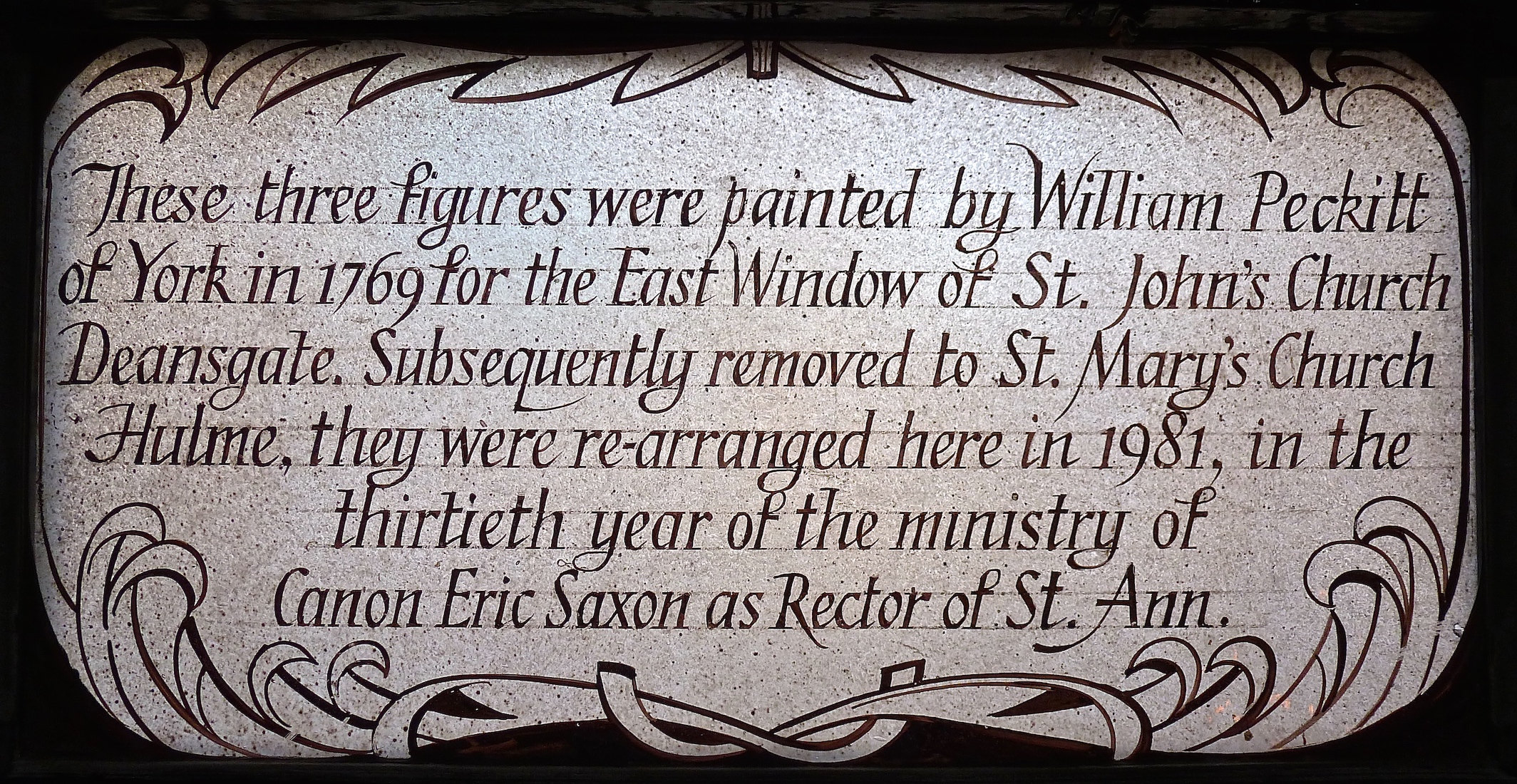

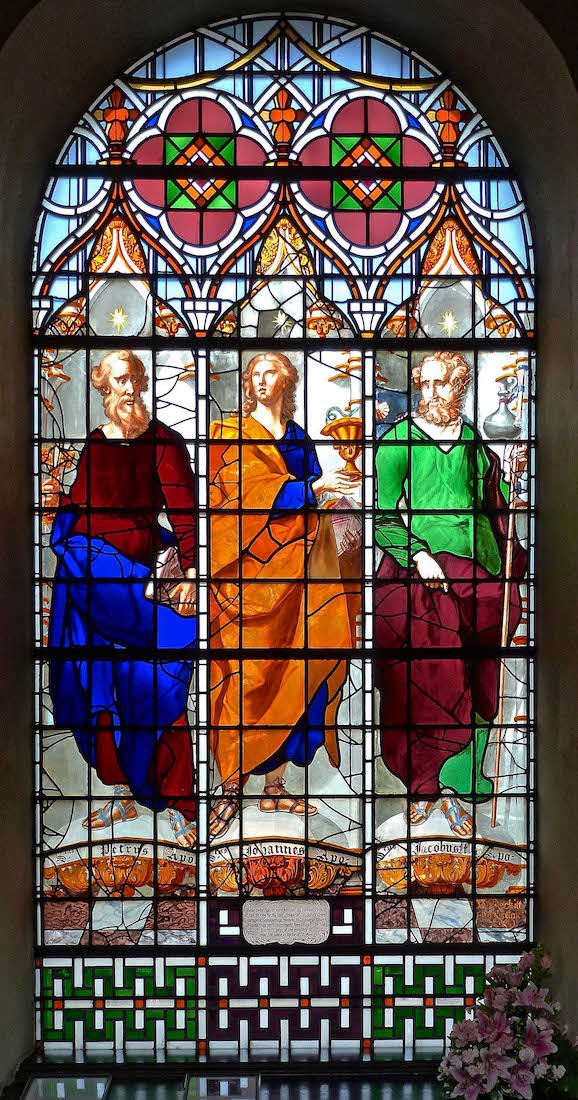

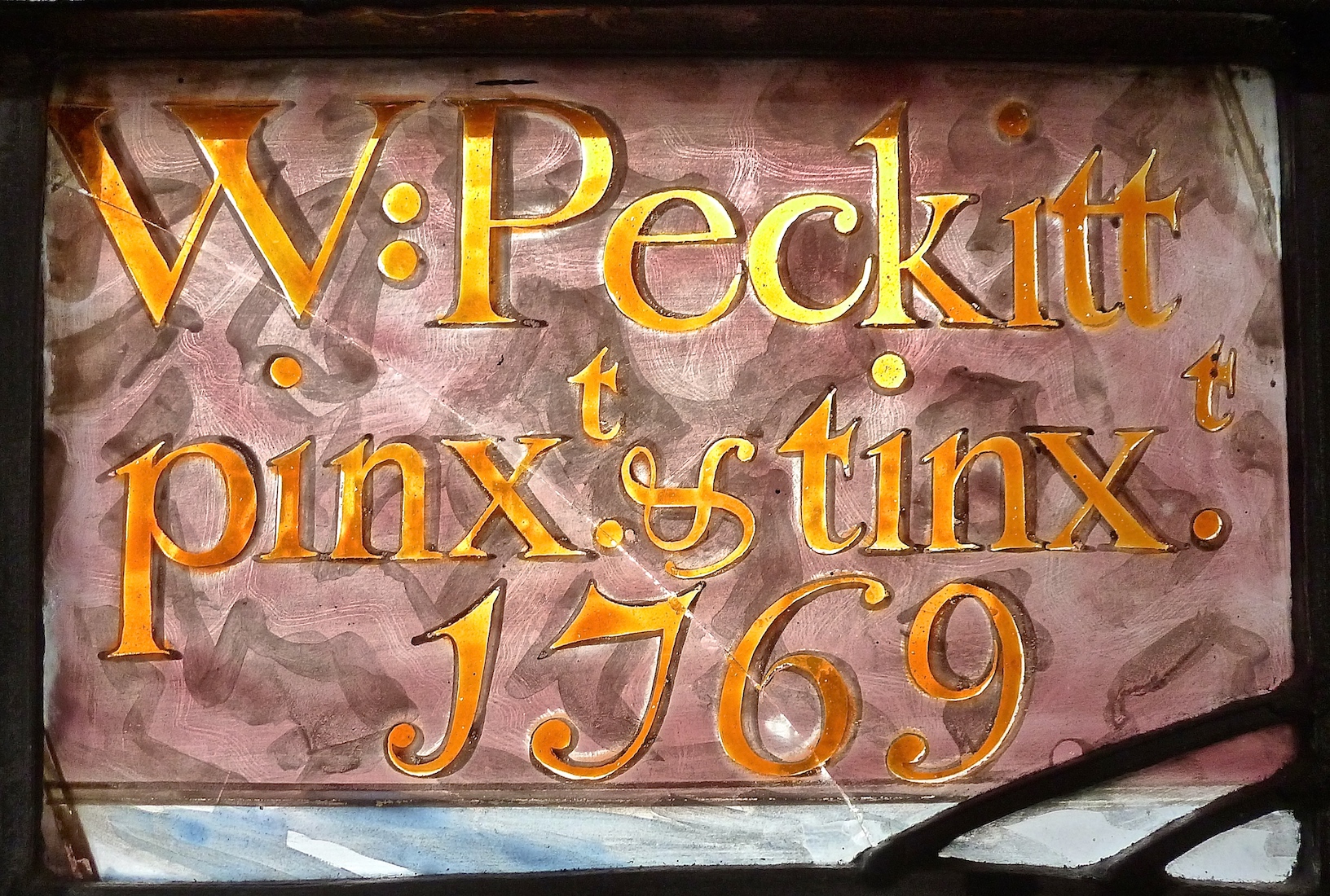

18. PECKITT WINDOW

The third window on this side is by William Peckitt (1731-1795). It shows St Peter, St John and St James – the disciples with Jesus at the Transfiguration. This window was not originally made for St Ann’s. It was saved from St John’s when that was demolished, then going to St Mary’s, Hulme before being installed in St Ann’s in 1981. William Peckitt was born in the village of Husthwaite, North Yorkshire. He became one of England’s most famous enamelled glass painters. By the time he was 30, he had gained a national reputation and included royalty and the nobility amongst his patrons. In his York workshop he executed stained glass for cathedrals, parish churches and secular buildings in many parts of England, York Minster, New College Chapel Oxford and the libraries of Trinity College Cambridge and Ripon Cathedral contain some of his most distinctive work. In 1768, the year before he painted the glass now in St Ann’s church, he married Mary the daughter of a York carver Charles Mitley. Mary assisted him in his work and after his death in 1795, she painted his memorial window in the church of St Martin-cum-Gregory, York, where this noted glass painter is buried.

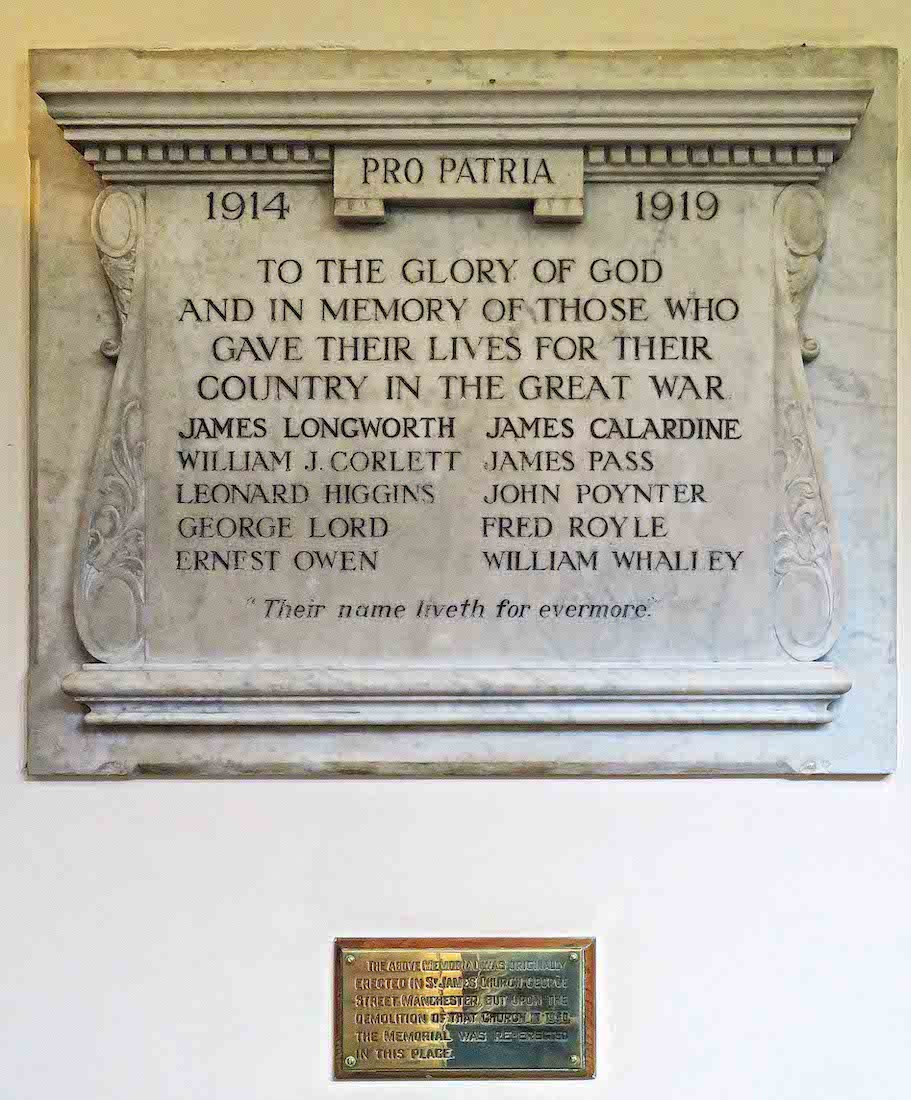

19. WAR MEMORIALS

Returning to the West end, we now look at the memorials on the North wall. These are both memorials to those who fell in the 1914–1918 War. The marble tablet came from the St James Church in Manchester when that was demolished around 1950. The second larger memorial commemorates those from the St Ann’s parish and congregation who gave their lives.

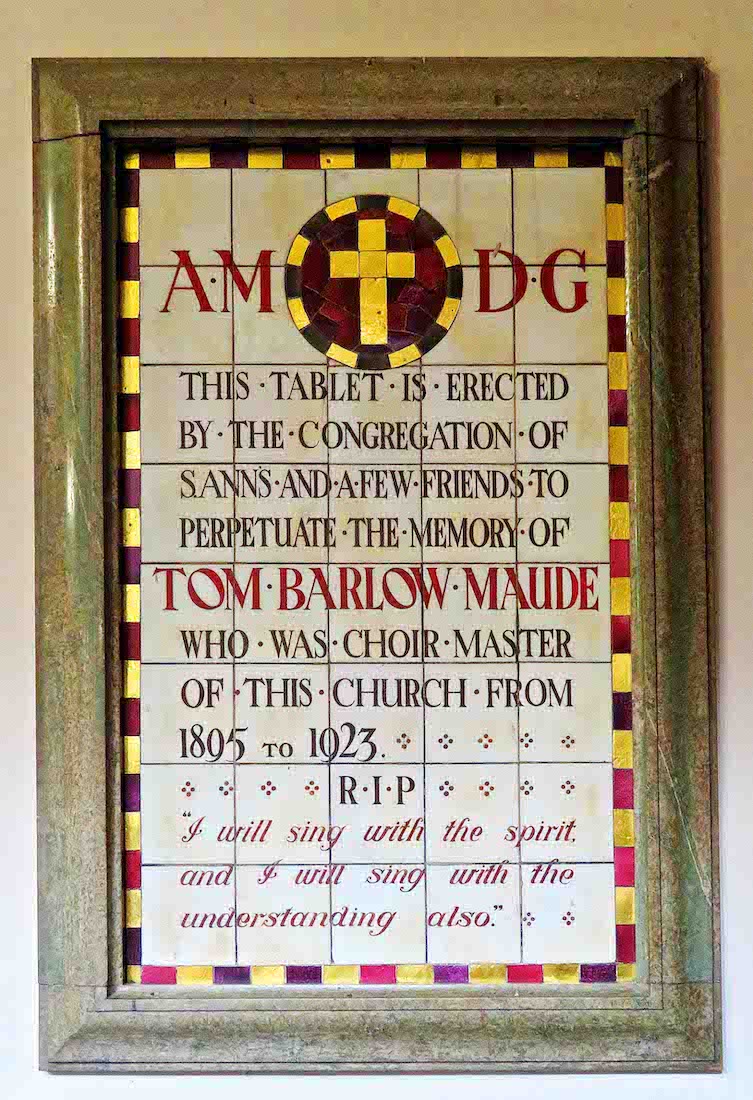

20. FURTHER MEMORIALS

The next memorial is to Rev Samuel Hall, who was first minister of St Ann’s, and who died in 1813. The final colourful tablet perpetuates the memory of Tom Barlow Maude who was choir master of this Church from 1895 to 1923.