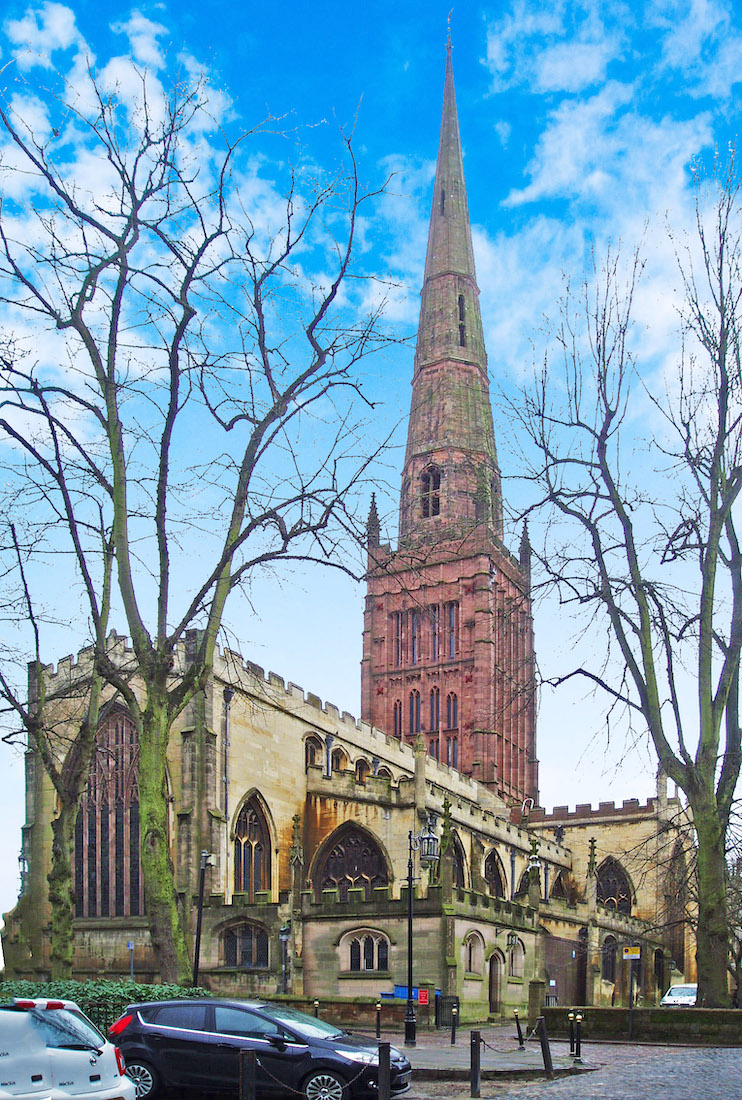

Holy Trinity Church is in the centre of the city of Coventry. It has an open garden area at its West end, but is rather enclosed by other city buildings. It lies within a stone’s throw of Coventry Cathedral: in fact the tower of the old St Michael’s (Cathedral) can be seen at the right of this photograph. It is surprising then, as we have seen, that the World War II Blitz which demolished the Cathedral left this Church relatively unscathed. This is a large Church. From this angle we see it has a high central nave with a nave aisle on either side, and then a further extension along the North (left) side. We shall walk around the Church in an anticlockwise direction.

2. STEPPING BACK AMT

The church dates from the 12th century and is the only Medieval church in Coventry that is still complete. It is 59 metres (194 ft) long and has a spire 72 metres (236 ft) high, one of the tallest non-cathedral spires in the UK.

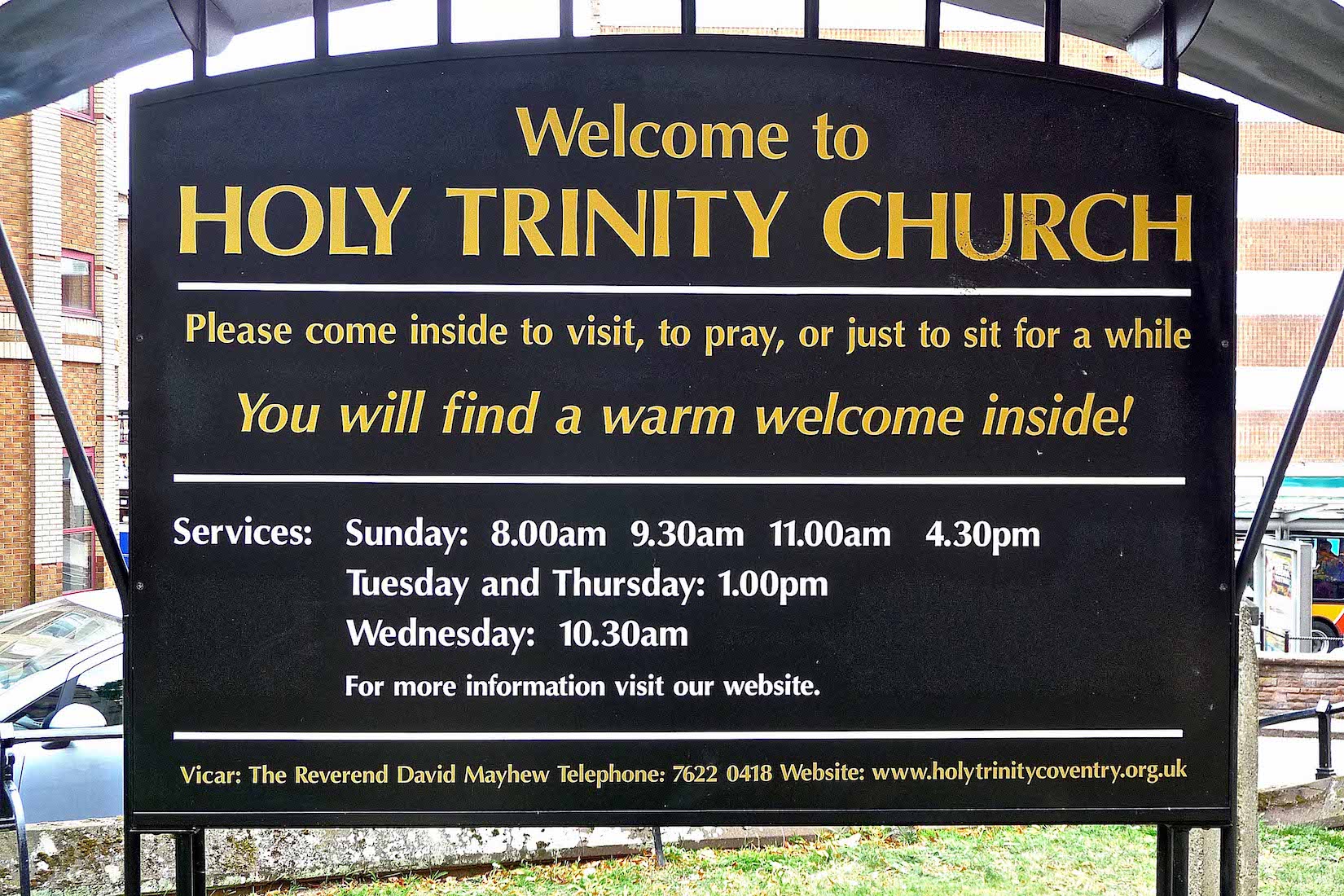

3. CHURCH SIGN GA

There is a fine welcoming sign at the front of the Church. We shall find plenty to see inside!

4. TOWER AND SPIRE AMT AMT

A fine tower like this makes one think of bells, but Holy Trinity has a rather sad history here. There were six bells until 1776, when a new ring of eight was provided. In the 1850s renovation of the Church, Gilbert Scott removed the floors of the tower to let more light into the building, and the bells were removed and hung in a wooden campanile to the side of the Church. The campanile was never strong enough to hold a ringing peal, and was taken down in 1966/7. After a decade in storage, the bells were finally sold to Christchurch Cathedral in NZ. However, that cathedral was disastrously damaged in the earthquakes of 2010 and 2011. A sorry tale! • The spire is topped off by an 8ft stainless steel weather vane in the form of a Dove of Peace. It was consecrated on January 25th 2001. It was designed by student John Clark as a tribute to Sir Frank Whittle, a brilliant aero engine designer, who was born in Coventry, but never really recognised in his field.

5. VIEW FROM COVENTRY CROSS AMT

This Southeast view of the Church was taken from Coventry Cross – a monument which sadly was removed in January 2019. We see how the South transept and the adjacent lower organ chamber extend out from the side of the Church. The Coventry Cross had a long history dating from Medieval times. An interesting note tells that in 1608–9 the City replaced a figure of Jesus with one of Lady Godiva! The Cross was removed as part of a plan to redevelop the area.

6. HIGH VIEW FROM SOUTHEAST AMT

This is an interesting overview of the Church from the Southeast. We might notice the variation in the building materials used in the construction, the unusual design by Gilbert Scott of the tower at the base of the spire, and the different shapes of the North and South transepts.

7. EASTERN WALL GA

The Eastern wall of the Church demonstrates a pleasing symmetry. Notice the low profile of the vestries alongside the sanctuary.

8. NORTHEAST VIEW AMT

We continue our walk around the Church. The castellation of the parapets was a dominant building style of the time. There are a number of old trees around the Church, but it is hemmed in by the various neighbouring city buildings.

9. AROUND TO THE WEST AMT GA

We walk along narrow Priory Row to the North of the Church, alongside a raised embankment with scattered headstones. We pass the North transept, the Peace Chapel, and the North porch, finally returning to the West wall from where we began.

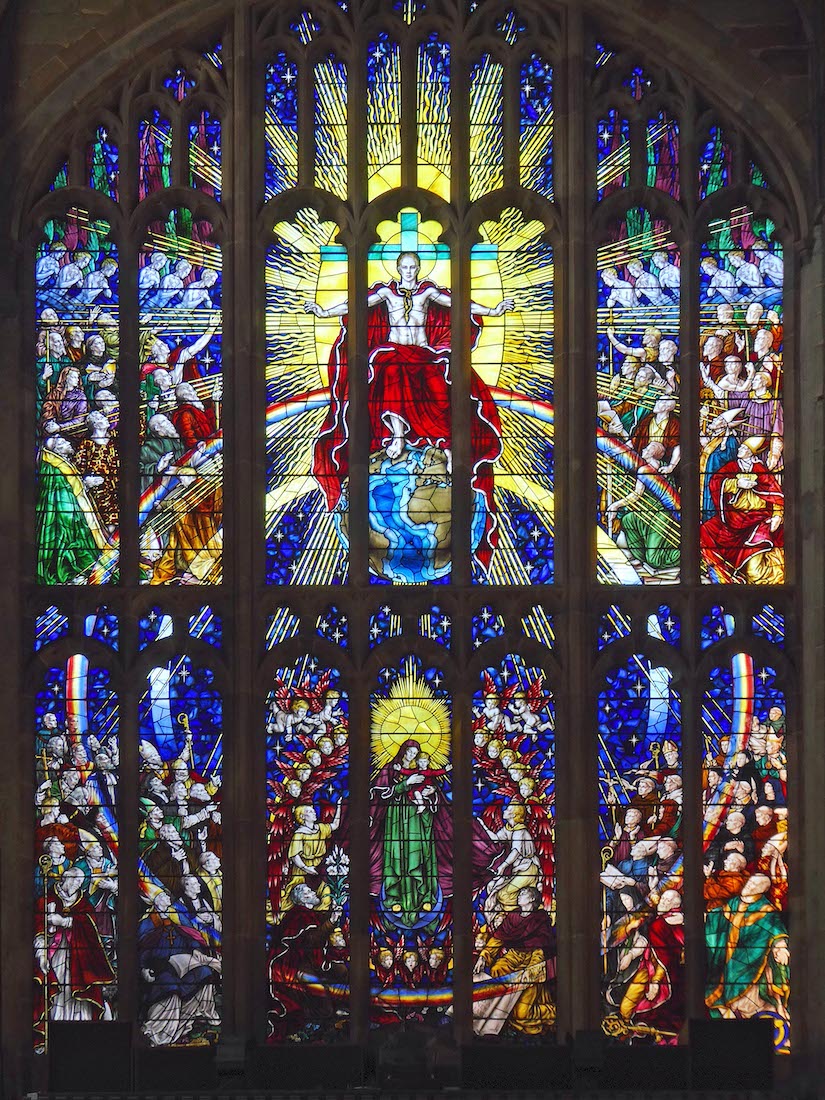

10. WEST WINDOW GA

The West wall features a large stained glass window: we look forward to viewing this from inside the Church.

11. WEST DOOR GA

Below the window is the West door, welcoming us in.

12. NAVE GM

The West door opens to a shallow wooden porch which in turn leads to a breath-taking nave. The nave is wide and light with high Gothic arches drawing our eyes to the crossing and sanctuary beyond. To the right are large clear quatre-foil windows, and immediately in front of us a large clear area dominated by a central raised font. Above the arch to the crossing is a mysterious painting ... .

13. FONT TO EAST WINDOW GA

Moving closer to the font, we gain a better idea of the painting. We also observe the old raised pulpit on a column at right. Ahead is an impressive stained glass window for later investigation.

14. FONT LOOKING WEST GM

From a little further down the central aisle we look back to the West wall. Nearest us are the carved poppy-heads of the pews. A stand in front of the font provides details of the colourful West window. Against the entry porch and to the right of the font we can see an interesting stoup. The arches at left open to the South nave aisle which appears to hold little of interest. However the arches at right lead through to the Archdeacon’s Chapel which we will investigate shortly.

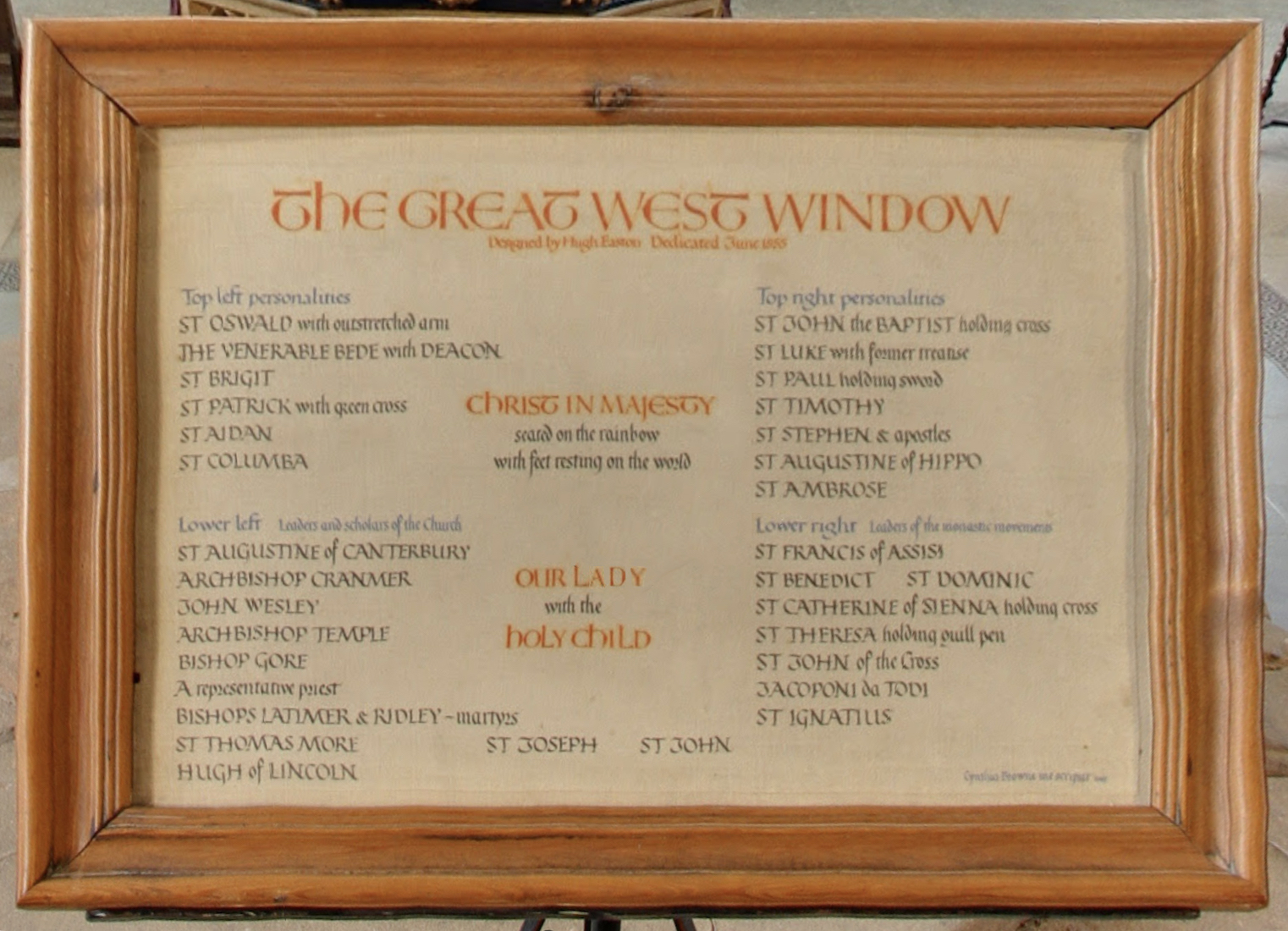

15. WEST WINDOW AMT GM

This is the Great West Window (or ‘Te Deum’ window). It shows Christ in Majesty seated on a rainbow, while around him are historical figures of the Christian Church. The window was designed by portrait artist Hugh Easton (1955) to replace a Victorian window destroyed by bombs in 1940. Click here for a zoomed in view of the window.

16. ARCHDEACON’S CHAPEL GM

This chapel can be dated back to before 1350 when it was used as a chapel in the medieval church. It was later used as a ‘Consistory Court’ where the archdeacon and his staff heard cases of moral, matrimonial and ecclesiastical problems within the church. The annual Archdeacon's visitation (when churchwardens are sworn in) also used to take place here. The roof dates back from the fifteenth century. Monuments formerly in other parts of the church were re-sited here during the restoration in 1854 - 1856.

17. ANGEL AND WINDOW ATM ATM

On the North wall of the chapel is this creative angel memorial to Vicar and Curate John Howells who died in 1857. • A nearby window on the North wall contains fragments of Medieval glass from the ‘Godiva Window’ which was originally on the South side of the Church. Church records tell us the Church windows were rich in medieval glass, but sadly the reformers destroyed much of this in the sixteenth century. These fragments are all that remain.

18. VICARS BOARD GM

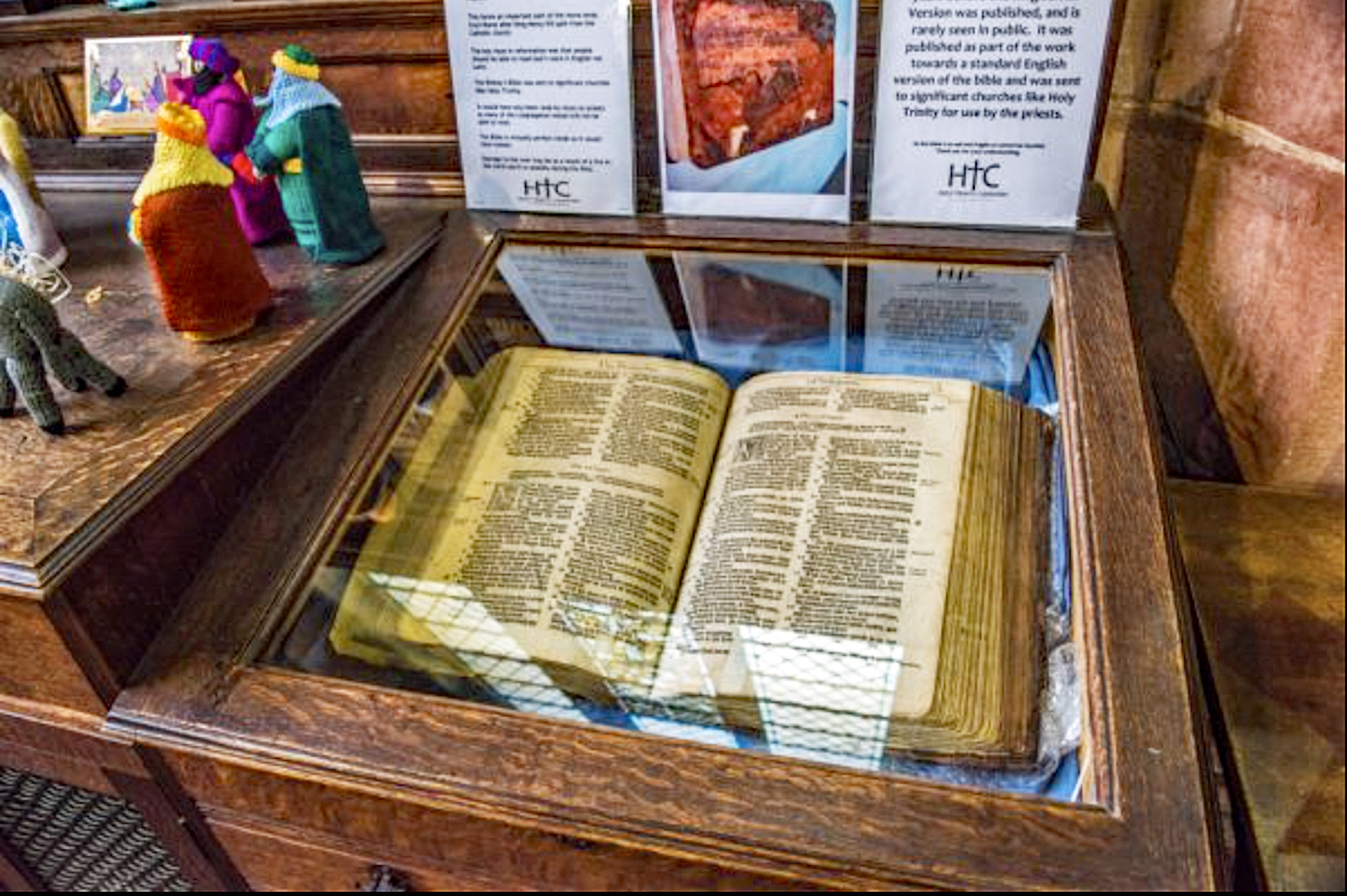

On a cabinet against this North wall is a list of Church vicars – including John Howells! A history dating back to before 1298 is quite incredible. • Beneath the glass panel on the right of the cabinet is a very old Bible.

19. BISHOPS’ BIBLE BE WH

With the accession of Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) in 1558, the restored Church of England required a new English translation to replace the controversial ‘Geneva Bible’ and its less popular predecessors. A committee of seventeen ecclesiastics and biblical scholars led by Matthew Parker (1504–1575), Archbishop of Canterbury, produced the new text. Royal decree then required that the “Bishops’ Bible” be placed in every cathedral and parish church. [First Photograph: Britain Express]

20. CHAPEL MONUMENTS AMT

A great number of memorials and monuments are displayed in the Northeast corner of the Archdeacon’s Chapel. We shall look at some of these ... .