Welcome to this talk! I have a great love for cathedrals – some might say ‘addiction’ or ‘obsession’, and they would probably be right! Whatever, I am always happy to share my cathedral experiences. So I invite you to come on a journey with me.

Shown here is a very famous cathedral, which is ... ? Yes, Salisbury Cathedral, as seen across the Avon. Not the ‘Stratford-on-Avon’ Avon. There are many Avons across England. This is because ‘avon’ is the Celtic word for ‘river’.

2. GEOMETRY

A word or two about my background. In real life I was a university mathematician – three years at Wellington University, NZ, and then the rest of my career at the University of Adelaide. My favourite part of mathematics was always geometry – the ideas of shape, space, angle, pattern – all ideas which appear in cathedrals! These models in my study are a reminder of times past.

3. FRACTAL GEOMETRY : MANDELBROT SET

Later in my career I became interested in fractal geometry and chaos theory. More sophisticated geometry, and involving computing. In fact around 1999 I had become involved in another type of computing: creating websites, although they were all mathematical in content, looking forward to online mathematics.

4. NEW HOUSE

Our cathedral journeys really began in 2012. We had just moved house, moving into a unit in a retirement village in Campbelltown.

5. ST PETER’S CATHEDRAL

As well, we had joined up with St Peter’s Anglican Cathedral, after a lifetime of involvement with the Baptist Church. So it was an unsettling time, a time of change, and time for some new beginnings. So I suggested to my wife Marg, that we take on the project of visiting and photographing in detail all 53 Australian cathedrals. I would produce a photographic website of each. It would take us to many towns and cities in Australia that we would otherwise never visit, and it would be a lot of fun. So we did, and it was! It took us seven years, and in the meantime we also photographed all the cathedrals in New Zealand, England, Wales as well as many across Europe. Over 160 altogether!

6. WHAT IS A CATHEDRAL? WINCHESTER AND MURRAY BRIDGE

So let us ask, ‘What is a cathedral’? Many people would answer ‘a big church’, which is usually right, until you visit the little Anglican Church in Murray Bridge, South Australia. ‘St John the Baptist Cathedral’! So size is not the determining factor ... .

7. CATHEDRA: WINCHESTER AND MURRAY BRIDGE

In the Anglican and Roman Catholic traditions, churches are grouped together, usually by location, into dioceses. There is a priest in charge of each church, and then a bishop who has oversight of all the churches in the diocese. One of the churches – usually the biggest and best! – is selected as ‘the bishop’s church’ or ‘the seat of the bishop’. More specifically, this last term refers to an actual seat or ‘the bishop’s throne’. The Latin word for ‘seat’ is cathedra (with no l), so a cathedral is a church which houses the cathedra. If you ever visit a cathedral, you might look out for this special seat.

8. CATHOLIC CATHEDRAL IN ARMIDALE, NSW

Come with me now to the country town of Armidale in New South Wales. There are two interesting cathedrals in this town: this one is the Catholic Cathedral of St Mary & St Joseph. There are several different crosses attached to this cathedral, and I’ll come back to this. But first there is a story! There is always a story!! I had photographed this cathedral and produced a website. As is my custom, I wrote to the Cathedral, informing them of what I had done. I received an email back from the Administrator, asking if the cathedral could buy my photos to use for Cathedral advertising and promotion. I wrote back saying No, but they could just use them for free. I then added, jokingly, that they might like to make me a saint! I received a serious reply: Ah Paul, sainthood is a very difficult process. It takes a long time, and is very expensive, ... . He forget to mention that martyrdom is a big help! I laughed, but even more when his next correspondence arrived: Dear St Paul ! Now, these crosses ... .

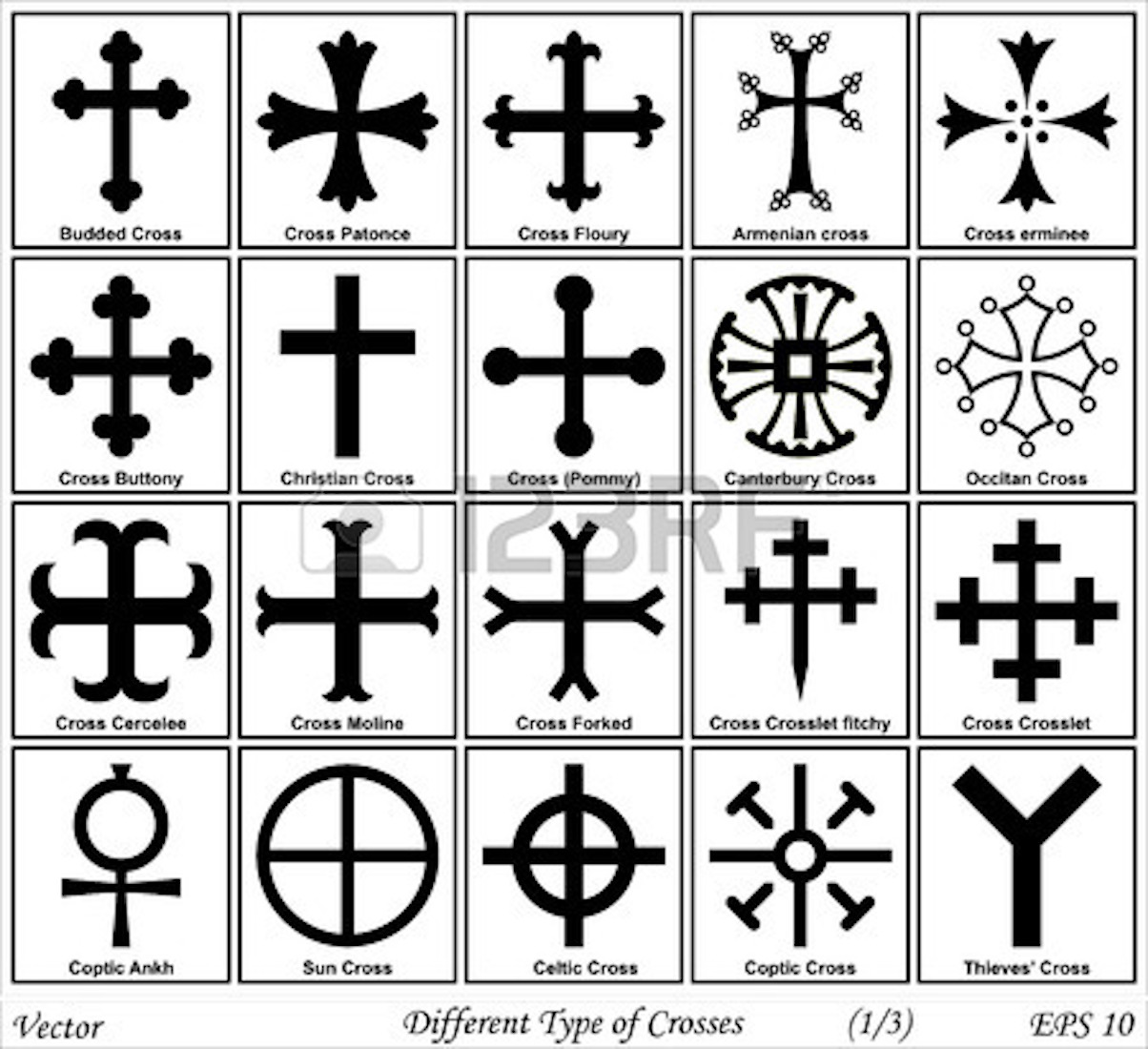

9. CROSSES

The cross at left is the universal symbol of the Christian faith, speaking of Christ’s death and sacrifice. However, crosses occur in a multitude of different shapes, of which some – and only some – are shown at right. Of these, the Budded Cross is often seen adorning old churches, and the Celtic cross (cross with superimposed circle – probably the sun originally) is well known. I would like to say something about the Canterbury Cross.

10. CANTERBURY CROSS, SINGAPORE

The Canterbury cross, designed after an Anglo-Saxon brooch (c 850) was found in Canterbury in 1867. In 1932 a Canterbury cross set in Canterbury stone was sent to every Anglican cathedral throughout the world as a symbol of unity, communion, fellowship. If you visit an Anglican cathedral, look out for one of these.

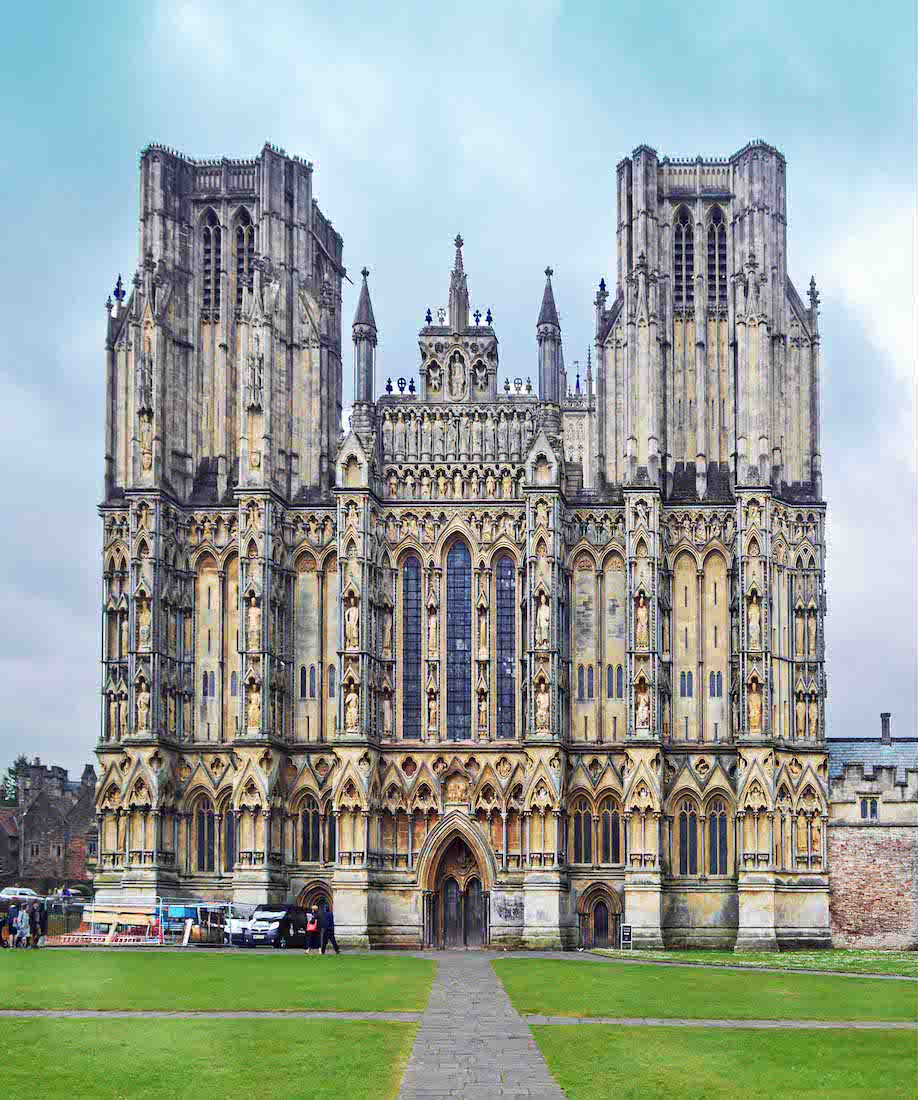

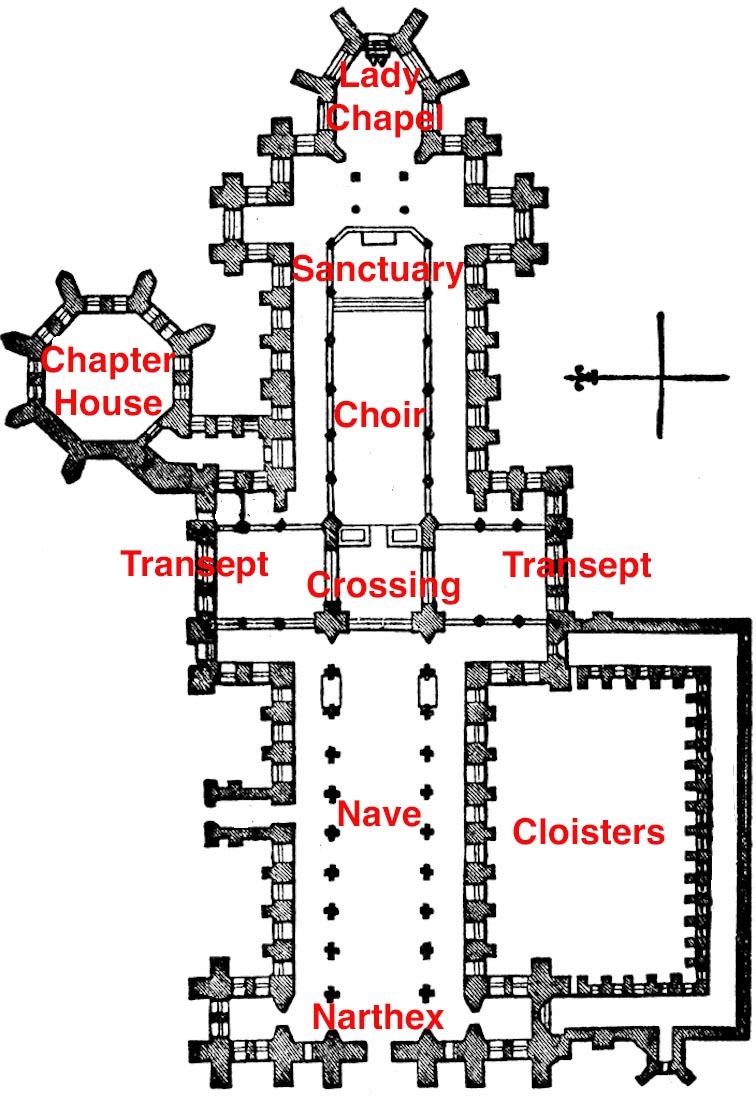

11. PARTS OF A CATHEDRAL : EXAMPLE WELLS

The cross is a part of the basic design of many cathedrals. Here at left is the West face of Wells Cathedral in England. And at right is the plan of the Cathedral. We notice the plan has a vertical axis, and a horizontal transept, these two parts forming a basic cross. Let us look at the component parts of this Cathedral. Entering by the West door (bottom of the plan) we come to the porch / foyer / or more generally narthex of the Cathedral. This leads through to the nave where the congregation sits. The transept(s) meet the axis of the Cathedral in the crossing, and beyond this is the choir and sanctuary. The choir and sanctuary are sometimes grouped together as the chancel. Often the choir and sanctuary extend to the Eastern (top) end, but there is often a Lady Chapel placed somewhere. If the Cathedral has a monastic history, we may also find a chapter house and cloisters. We return to these later.

12. WELLS CATHEDRAL NAVE : SCISSORS ARCH

We come into the nave of Wells Cathedral. People often exclaim to me how wonderful the early cathedral builders were, constructing these amazing buildings without modern technology, and the buildings still stand today. All of which is true, but not always! In the 13th century the original central tower of Wells Catheddral was damaged by an earthquake, and a new, bigger, better tower was constructed. Unfortunately the new tower was too heavy for its foundations and to avoid collapse, between 1338 and 1348 the ingenious scissor arches were added on three sides. These days the arches are a special attraction for visitors!

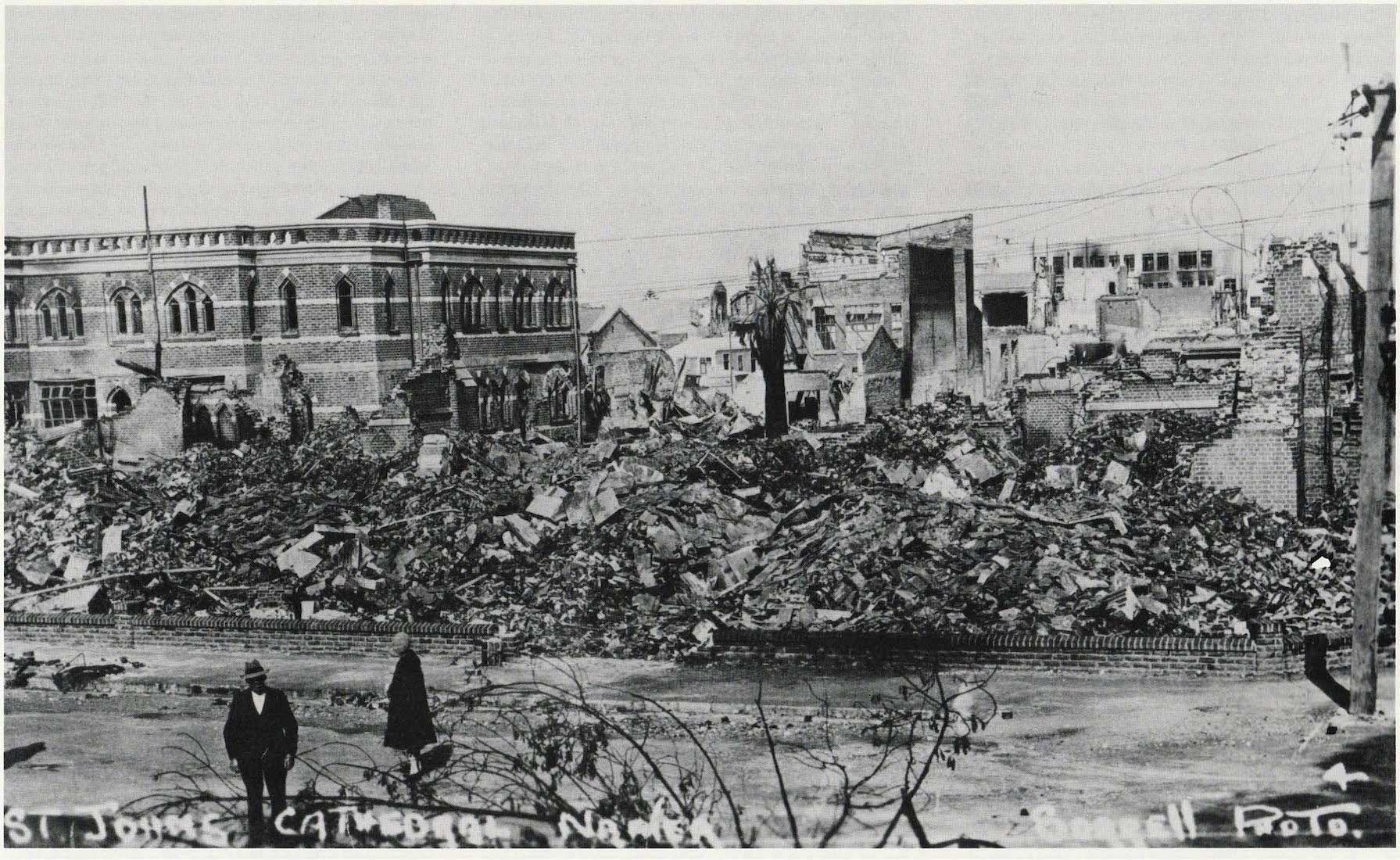

13. NAPIER RUINS, 1931

Other cathedrals have had unfortunate pasts. We might think of the recent fire in Notre Dame in Paris. But here we are in Napier New Zealand, after the 1931 earthquake. The heap of rubble is the cathedral. In fact the whole city was destroyed and then rebuilt in the architectural style of the time – Art Deco. Now Napier is the Art Deco Capital of NZ! I have a special connection here: my parents lived here, and were in the city at the time of the quake. Later I too lived in this city.

14. NEW NAPIER CATHEDRAL

The new Cathedral of St John the Evangelist, also known as Waiapu Cathedral, was built between 1955 and 1965. It is earthquake proof, being constructed of reinforced concrete. But I remember a lot of controversy about it at the time. It didn't look like a cathedral! Which raises the interesting question: What is a cathedral supposed to look like?

15. COVENTRY CATHEDRAL RUINS, 1940

Another cathedral with a sad past is Coventry Cathedral. The old St Michael’s Cathedral was reduced to rubble by German bombing in 1940. The rubble was removed, leaving the remaining outer walls standing. We visited this Cathedral long ago, in 1986, before I was interested in photographing cathedrals. I cried then, at the sheer stupidity of war.

16. NEW COVENTRY CATHEDRAL

The new Cathedral has been built right next to the ruins, and I remember going in and thinking, ‘Why did they bother?’! I have been back more recently to photograph the Cathedral, and have revised my opinion: the new Cathedral has many interesting features, and now has a wonderful ministry of reconciliation, built on its past.

17. PARRAMATTA CATHEDRAL FIRE, 1996

Closer to home, and more recent ... . The Catholic Cathedral of St Patrick in Parramatta, just out of Sydney, and dating from 1836, was gutted by fire in 1996.

18. NEW PARRAMATTA CATHEDRAL

The original building was recreated as a chapel, with an entry on its North side to a large new auditorium which became the new Cathedral. Modern, large, efficient ... but is it a cathedral?!!

19. THE FALL AND RISE OF BUNBURY CATHEDRAL: 2005 AND TODAY

And finally ... . Even more recent was the demise of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Bunbury, Western Australia. The Cathedral stood high on a hill overlooking the city, but was dislodged from its foundations by a cyclone in 2005. Declared unsafe, it had to be demolished. However, a new modern St Patrick’s has arisen in its place. The new cathedral is well done: modern and spacious, but with many allusions to traditional cathedral construction.

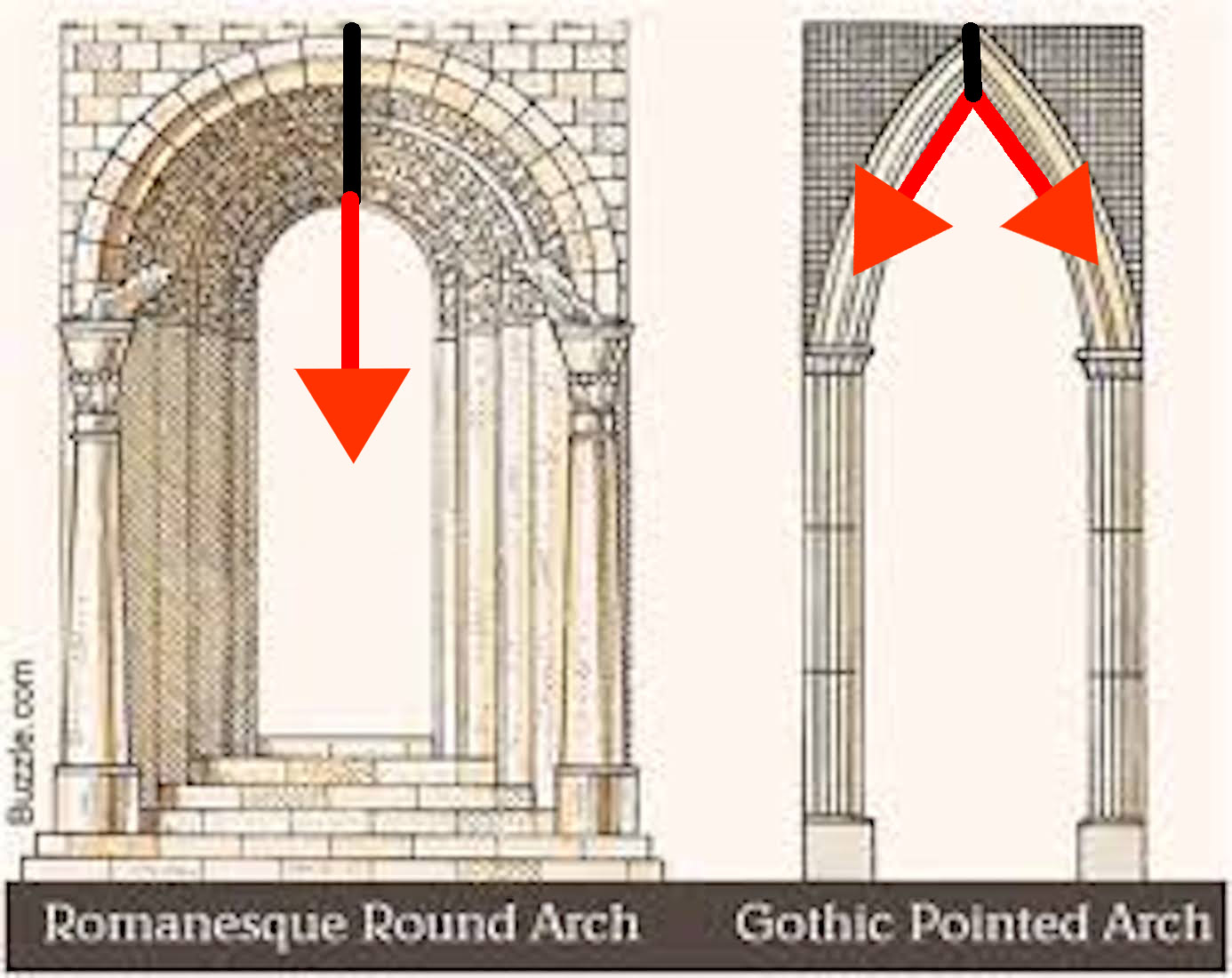

20. NORMAN AND GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE

Up until about 1200 AD, Cathedrals had been built in the Norman or Romanesque style. This is characterised by big solid columns and semicircular arches. (I love these arches: they are works of art!) After 1200 AD the Gothic style came in, characterised by tall graceful columns and pointed arches. The coloured arrows indicate the way the arches bear weight. At left, the weak point is the centre of the semicircular arch. For the Gothic arch, the downward thrust at the top of the arch is deflected to the sides. In practice, this means that the resulting downward thrust below the apex of the arch is less: some of the thrust has been converted to a horizontal component. This means that Gothic buildings can have narrower, more elegant columns. But there is a downside too!