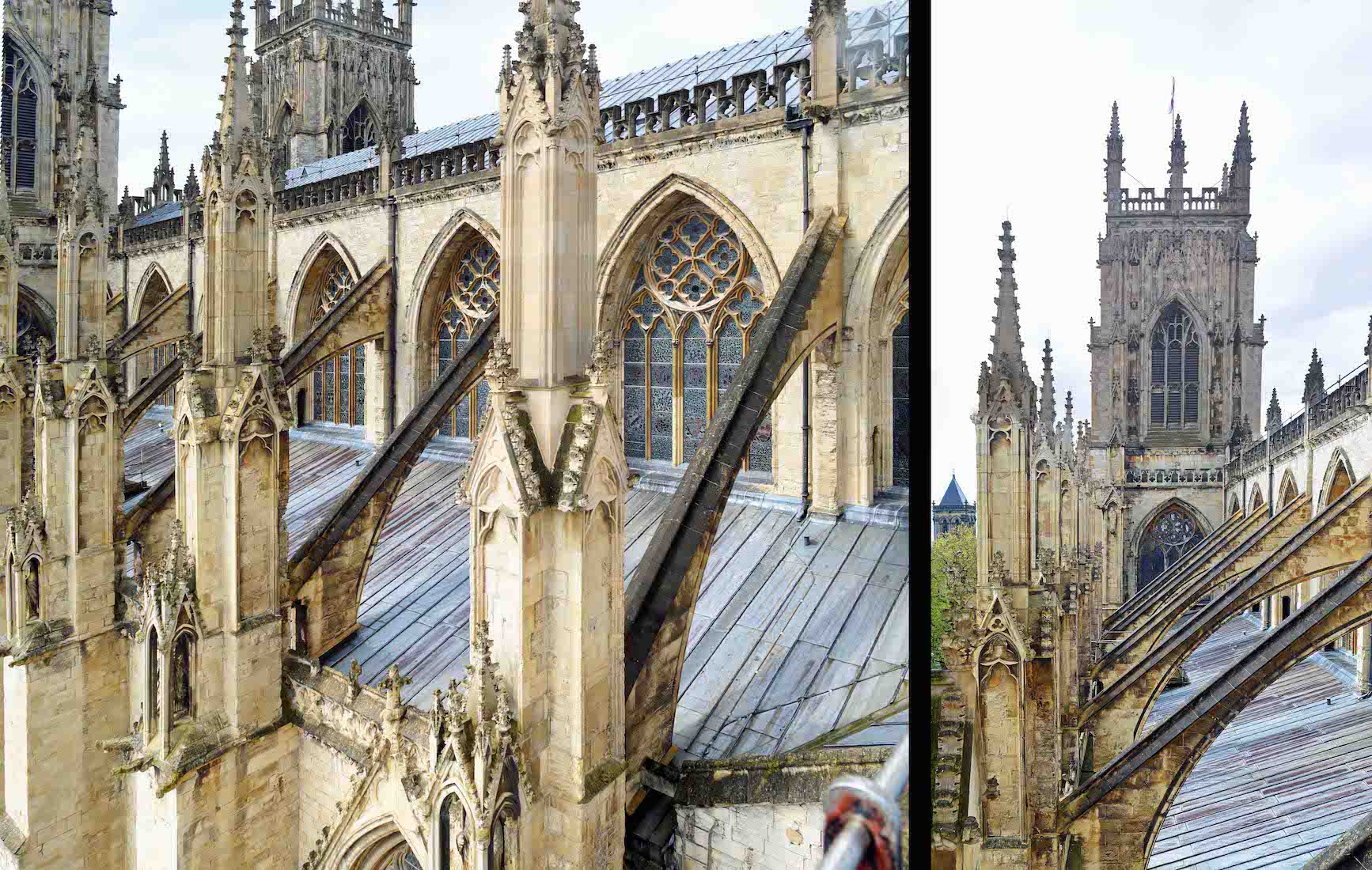

21. FLYING BUTTRESSES AND PINNACLES – YORK MINSTER

Because some of the downward thrust has been converted to a horizontal component, the tops of the columns are now being pushed out! Early builders compensated for this by introducing flying buttresses. Another feature of this construction is the tall pinnacles atop the supporting columns. I used to think this was just a nice Gothic decoration, but often these pinnacles were filled with lead – increasing the downward thrust on these supports.

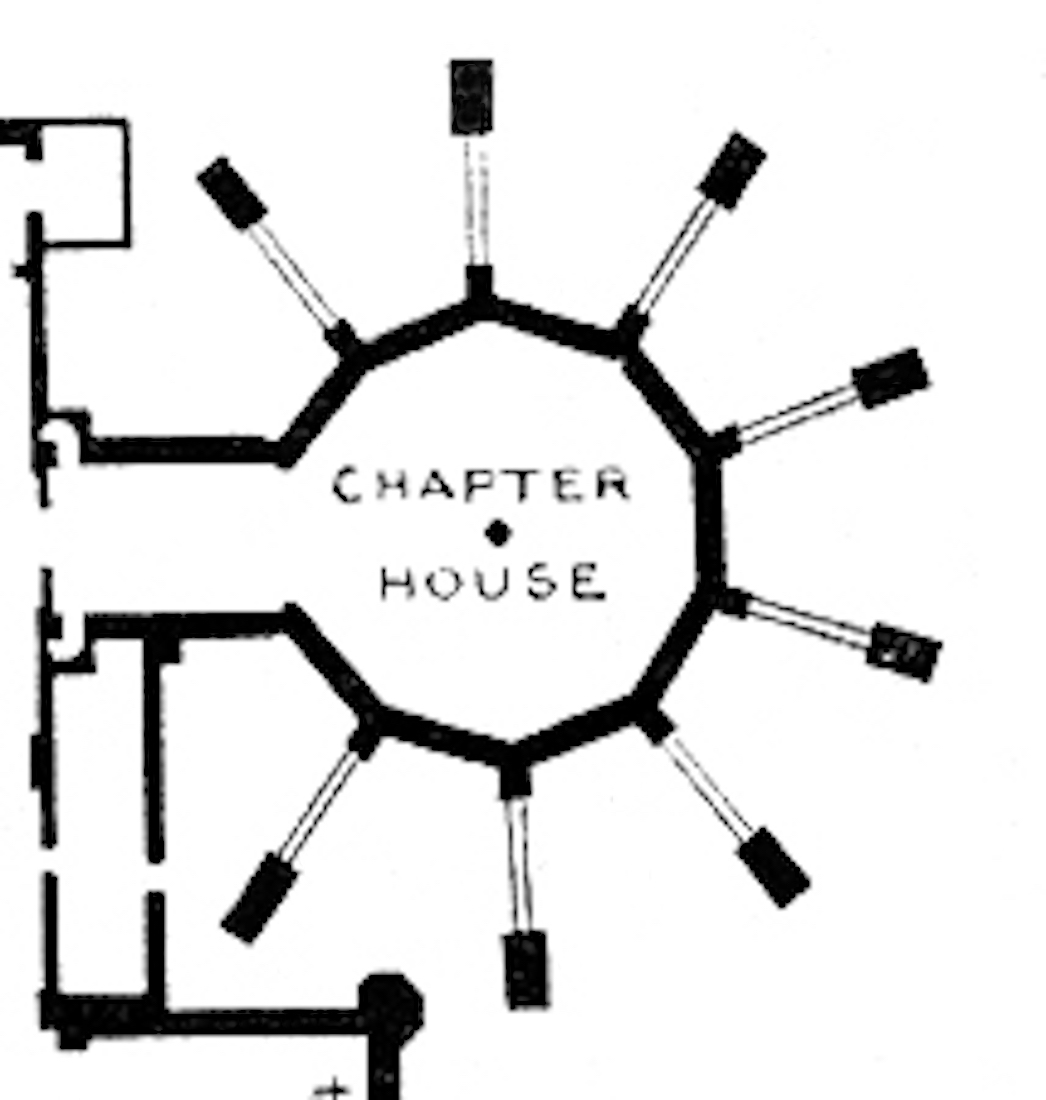

22. CHAPTER HOUSE – LINCOLN CATHEDRAL

Cathedrals which had once been part of a monastery frequently have a chapter house. This is normally an octagonal or decagonal building with a single entrance and outside window walls. The building has seating around the inside walls, and perhaps a lectern. At close of day, the monks would gather here and listen to a chapter read from the works of their founder – for example St Benedict.

23. CLOISTER: NORWICH CATHEDRAL

Another feature of monastic cathedrals is the cloister. This is a covered walkway, generally around a rectangular patch of grass. Arches looking towards the grassed interior would be open or glazed, sometimes with stained glass. This is where the monks would get their daily exercise – rain, hail or shine. In the case of England, probably quite a lot of rain and hail! This is the cloister at Norwich Cathedral.

24. LABYRINTH

The Norwich Cathedral cloister is of particular interest because it has a labyrinth in the middle. The labyrinth plan shown here is more complex than the Norwich labyrinth. A labyrinth is different from a maze: it is a single circular path (shown in black at right) which begins ‘outside the disk, and leads to the centre. It is an aid to meditation. For example you might start at the outside ‘in the world’, and make your way to God at the centre. The path is seldom direct, reflecting spiritual highs and lows. Having made your peace with God at the centre, you can then retrace your steps, returning to the outside world. In the photo at left, an ancient monk(my wife!) follows her path of discovery.

25. NAVE: NORWICH CATHOLIC

Let us look more closely at some cathedral naves. Whenever I visit a ‘new’ cathedral, I love to sit at the back and meditate for a little. For me, is this a sacred space? a spiritual place? a place where I might find God? This is the Catholic Cathedral of St John the Baptist in Norwich. This Cathedral has a special place in my journey. We had come to Norwich to photograph ‘the’ famous Norwich Cathedral. In the afternoon we took a bus tour of the city, and were driven past this other Cathedral which I knew nothing about. I fell in love with it, and my cathedral photography project was increased by a large number to include all the Catholic cathedrals!

26. NAVE: DARWIN CATHOLIC CATHEDRAL

Closer to home, this is the Cathedral of St Mary, Star of the Sea. It is not a cathedral which appeals to me, although it does have some very interesting features. As a geometer I am drawn to its parabolic arches – apparently strong enough to resist the destructive winds of Cyclone Tracey in 1974.

27. NAVE: TRURO CATHEDRAL

Then there is the Anglican Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Truro, Cornwall. I love this Cathedral because it has a kink at the crossing. You can see that past the end of the central nave aisle, there is a distinct 5° kink to the left. How did this happen? The Cathedral was built on the site of the 16th century parish church of St Mary the Virgin. When the Cathedral was built, the choir / sanctuary were placed to include the old church as a chapel. Then later when the nave was added, they found the proposed design just failed to fit on the Cathedral property, so it was added at a slight angle!

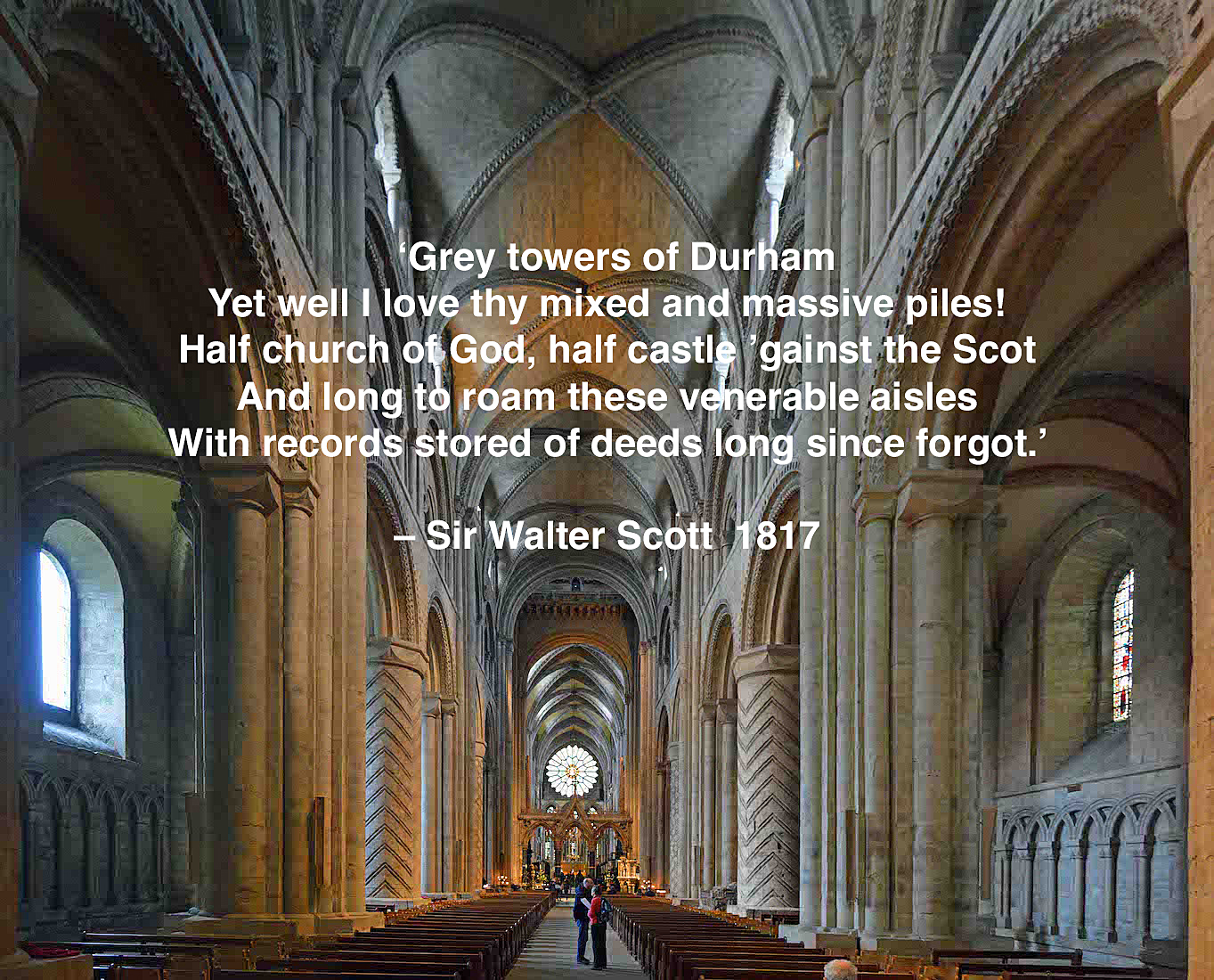

28A. NAVE: DURHAM

Any English cathedral hunter has to visit Durham Cathedral! Gothic influence can be seen, but the near nave is decidedly Norman, with its large patterned columns and round arches with edges dec orated with a chevron pattern. I always think of Sir Walter Scott’s ‘mixed and massive piles’.

28B. NAVE: DURHAM

In these words of Scott, I pick up on the ‘venerable’, thinking of the Venerable Bede (673 – 735) who was associated with this Cathedral. In fact he can be seen lying in state in the Galilee Chapel, West of the nave. We attended a short service there during our visit, and I have to report that the Venerable Bede slept right through it! A very poor example!

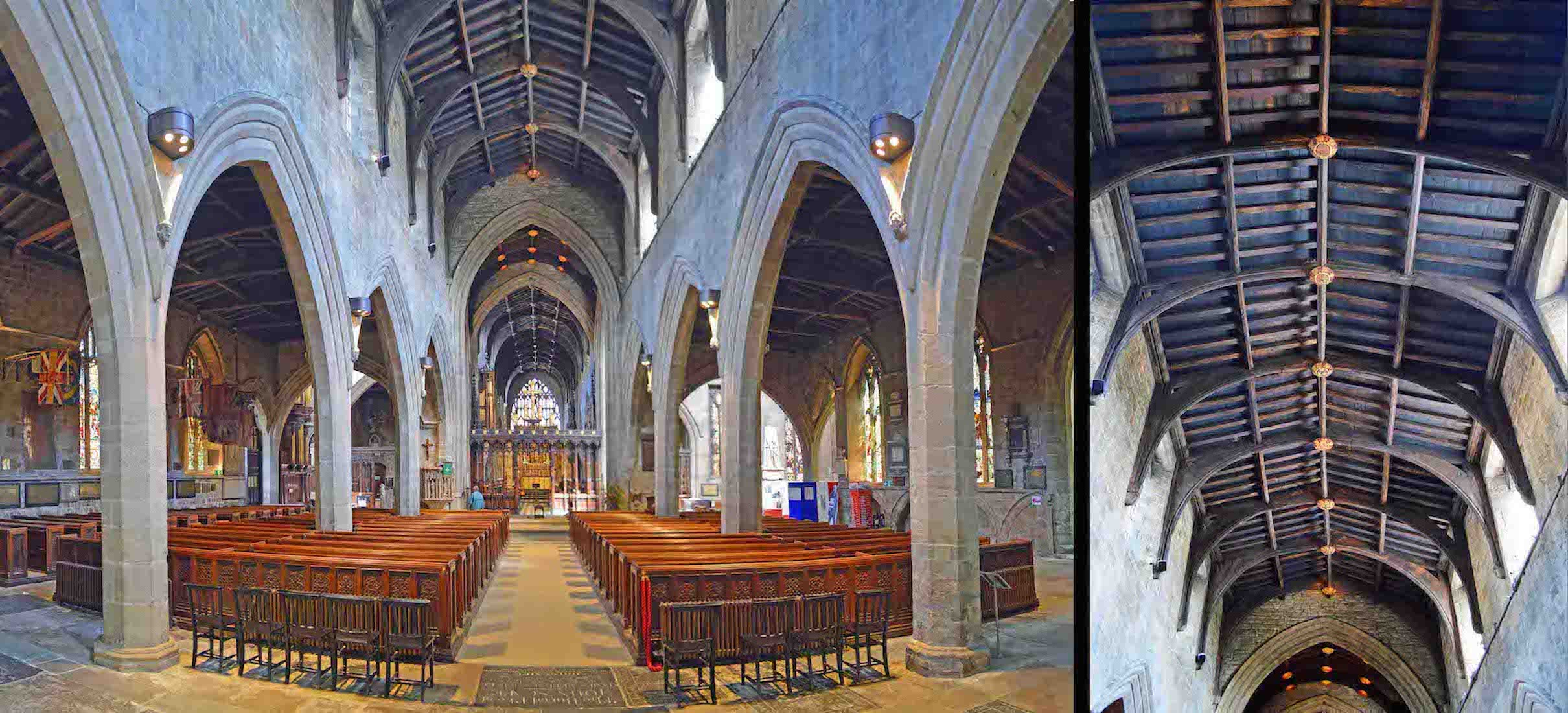

29. WHY ‘NAVE’?

Where did the nave get its name? Here we are in the St Nicholas Cathedral in Newcastle-on-Tyne. The nave ceiling shown at right closely resembles the inverted hull of a ship. This is the link: ‘navis’ is Latin for ship. Our word ‘navy’ also derives from this.

30. TRANSEPT

Coming to the front of the nave, the transepts are on either side of us. The transepts have no particular role to play. Large congregations in St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey can be seen overflowing into the transepts. On the other hand, if you happen to have a large astronomical clock, what better place to put it! This clock is in the South transept of Durham Cathedral.

31. CRYPT I

I haven’t mentioned the crypt: a large basement space beneath many cathedrals. This is a good place to talk about the crypt, because the entry is often from a transept. Sometimes, as here in St Paul’s Cathedral, the crypt contains a collection of memorials, monuments, tombs and effigies.

32. CRYPT II

On the other hand, if you visit the crypt of Winchester Cathedral, you might think of taking your gumboots! Around 1900, Winchester Cathedral was in danger of sinking into the ground. But between 1906 and 1911, deep sea diver William Walker came to the rescue. Working 6 metres under the water, Walker shored up the Cathedral foundations with 25,800 bags of concrete, 114,900 concrete blocks, and 900,000 bricks, thus saving the Cathedral. A mammoth effort! His memorial is in the cathedral.

33. PETERBOROUGH CROSSING

In a cruciform shaped cathedral, the crossing is the place where the transept crosses the long axis of a cathedral. The crossing often has a very attractive ceiling, as here in Peterborough Cathedral.

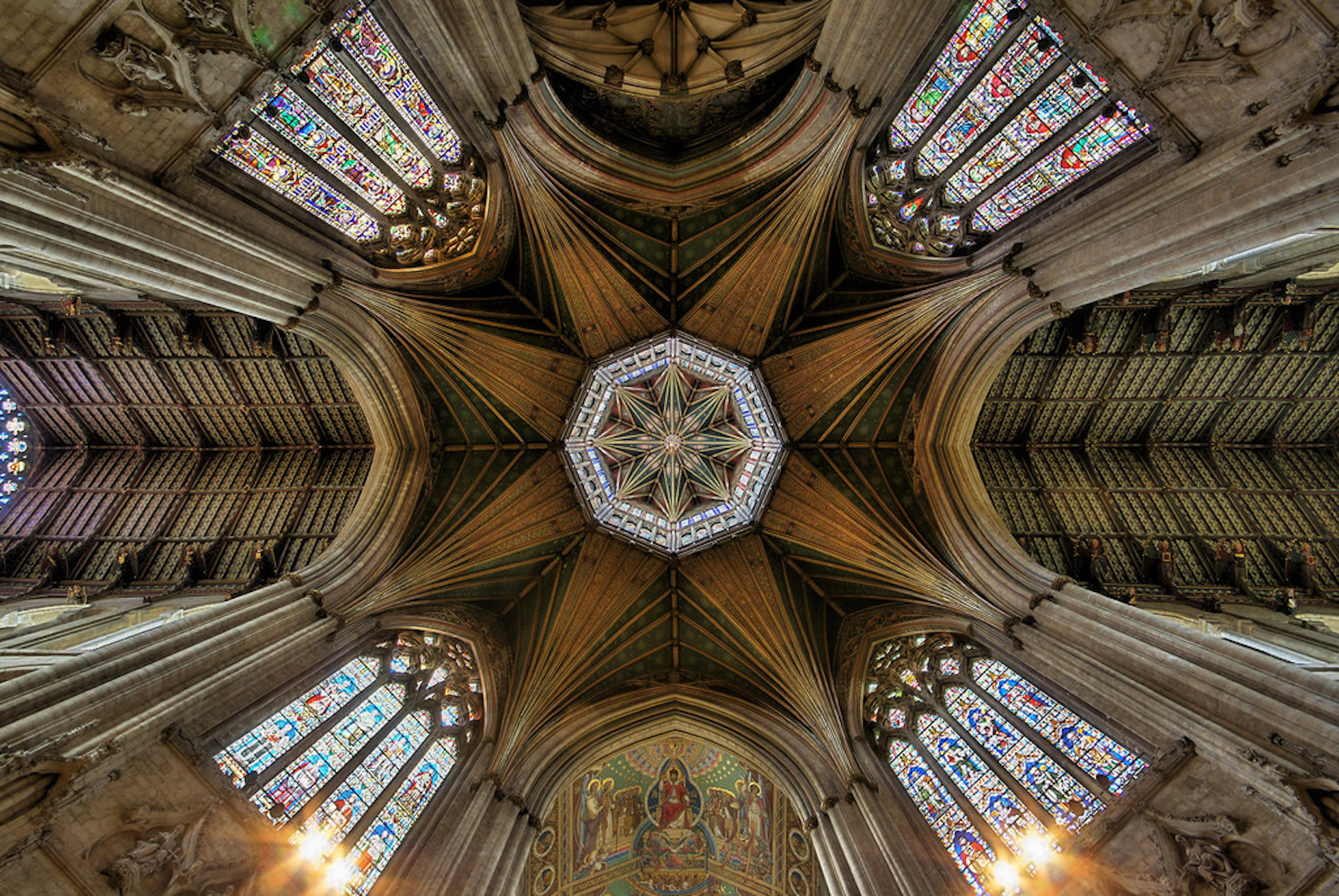

34. ELY OCTAGON

Above the crossing at Ely Cathedral is the spectacular Ely octagon / lantern. As with Wells, this cathedral wonder was the result of a disaster: the original Norman tower collapsed in 1322, and was replaced by this largely wooden structure. The design is so successful, I wonder why other later cathedral builders didn’t use the idea. You can take a tour to the top of the lantern.

35. SALISBURY CROSSING

Where there is a tower or spire above the crossing, there will be a trapdoor through the crossing ceiling to allow the passage of building materials up and down. Such a trapdoor is often disguised, but not here in Salisbury Cathedral.

36. SALISBURY CATHEDRAL HOIST

This is how materials were hoisted up and down in Salisbury Cathedral in the olden days. A hamster wheel, with men walking around it ... .

37. SALISBURY CATHEDRAL SPIRE

And this is the inside of the Salisbury spire.The spire was built in 1320, is the tallest in Great Britain with a height of 123 metres, and has a lean of 75 cm. I’m surprised it is still standing at all!

38. PULPIT AND LECTERN

The crossing is where we usually find the pulpit and the lectern. From the pulpit the Gospel is preached week by week. And the lectern holds the Bible, which is read from here. The brass eagle is a common form for the lectern, with the Scriptures supported by the eagle’s wings. I think no one knows the reason for the eagle, apart from centuries of church tradition. It has been said that the eagle flies closest to heaven, that we shall mount up with wings as eagles (Isaiah 40:31), that the evangelist John has the eagle as his symbol, ... but I am not convinced by any of these explanations.

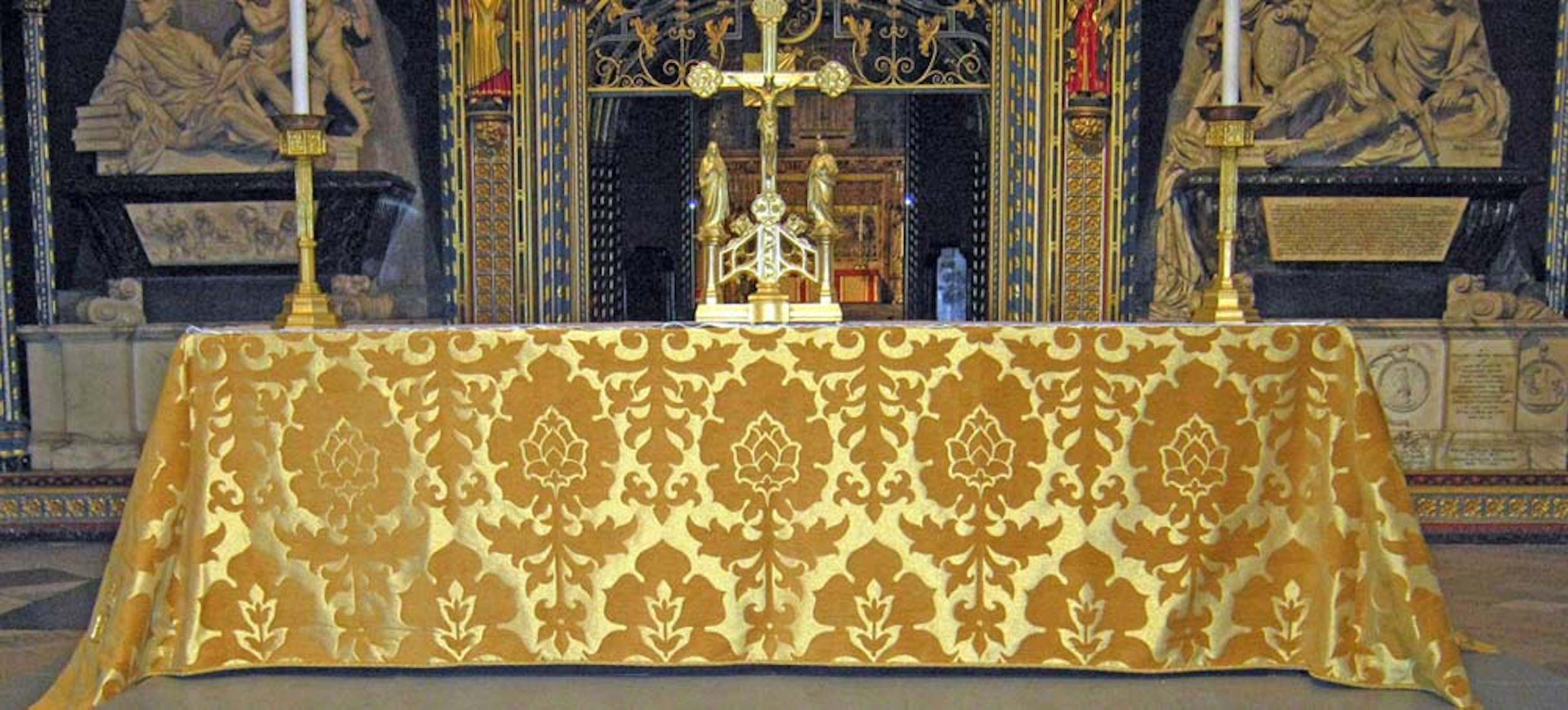

39. NAVE ALTAR

And then there is often an altar (or communion table) in the nave – the nave altar. We shall comment on this later.

40. RIPON PULPITUM

Beyond the crossing is the chancel, or choir and sanctuary. There is a separation from the nave by a screen – usually light-weight, but occasionally solid like this pulpitum of Ripon Cathedral. We can see the screen as arising from monastic times. The monks would hold their services sitting in the choir stalls, and over time people from nearby villages would want to join in. They would sit in the nave, and never the twain shall meet! The organ is often placed centrally as here, providing music to both sides of the screen.